By Katía Truijen

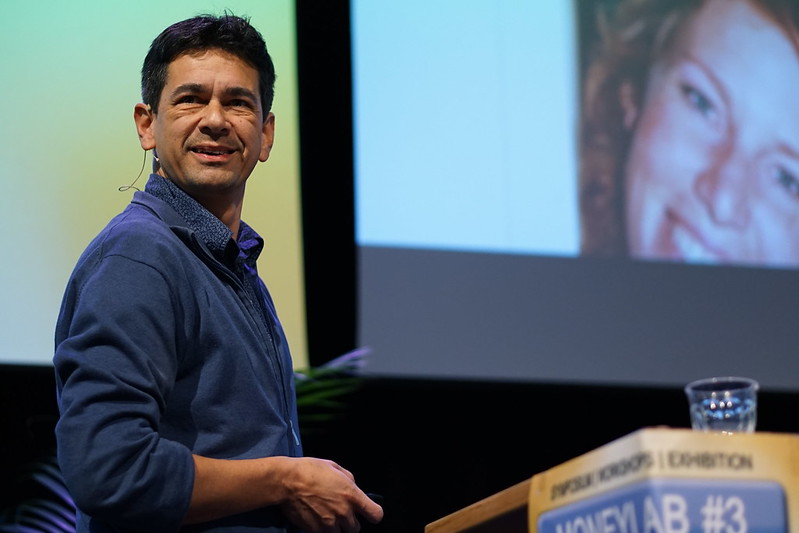

Sabine Niederer, director of CREATE-IT, introduced the first speaker Trebor Scholz, who has coined the term platform cooperativism. Scholz is a scholar-activist and associate professor for Culture & Media at The New School in New York City. Developing an analysis of the challenges posed by digital labor, he introduced the concept of platform cooperativism as a way of joining the peer-to-peer and co-op movements with online labor markets, focusing on re-establishing communal ownership and democratic governance structures. In his talk, he provided the audience with a crash course on platform cooperativism while presenting some tangible examples that have emerged over the last year.

MoneyLab #3: Sabine Niederer. Cooperatives and the Commons from network cultures on Vimeo.

Scholz explained that, in order to understand the emergence of platform coops, one has to look back at the last forty years in which employment has increased inequality. He expressed his concern about the 50 million independent and domestic workers in the United States alone, who have emerged since the financial crisis in 2008, and who do not have any workers rights. Around the same time, the so-called “sharing economy” emerged, with services as such as Blablacar and CouchSurfing offering networked co-operative organisations for transport and accommodation. But these new services were rapidly succeeded by more ambitious profit driven companies that aimed to capitalize on the sharing values of these initial start ups and expand into global infrastructure. A critique on the sharing economy has now even become mainstream, as working conditions have become a seriously problem with apps like Uber & Airbnb that are violating local and regional laws.

Scholz explained that, in order to understand the emergence of platform coops, one has to look back at the last forty years in which employment has increased inequality. He expressed his concern about the 50 million independent and domestic workers in the United States alone, who have emerged since the financial crisis in 2008, and who do not have any workers rights. Around the same time, the so-called “sharing economy” emerged, with services as such as Blablacar and CouchSurfing offering networked co-operative organisations for transport and accommodation. But these new services were rapidly succeeded by more ambitious profit driven companies that aimed to capitalize on the sharing values of these initial start ups and expand into global infrastructure. A critique on the sharing economy has now even become mainstream, as working conditions have become a seriously problem with apps like Uber & Airbnb that are violating local and regional laws.

According to Scholz, the distributed nature of what once was called the internet, is quite the opposite of the vision we see today. He noticed that critical analysis and activist projects exposing this, have often been too scholarly, while there has been a lack of projects of transition, or steps for people to take concretely. Especially in a time like this, Scholz argued, it seems that we are in need of initiatives that build society.

Platform cooperativism can be understood as a multi-stakeholder coop. The idea is to use the algorithmic heart of an app like Uber, and to replace it with a cooperative business model in which members have a democratic role. It also tries to establish a new role for unions, and invites existing cooperatives to reinvent themselves. It asks for a real commitment to the commons and free software, avoiding the pitfall of techno-solutionism. It promotes local self-organization, while trying to establish a diversified digital economy, that is not only ruled by monopolies. Lastly, it strives for data ownership and meaningful interoperability between cooperatives.

Scholz’ idea of platform cooperativism followed from the observation that there are in fact many coops out there, but people simply don’t pay attention to them. By now his website platform.coop has developed into a movement that brings together many projects around the world. For instance, local alternatives to Uber are emerging in many cities and are often quite successful. Other platforms like Loconomics offer independent workers the possibility to offer services and gain 100% of what they charge. Other promising platforms are Coopify and Fairmondo, as well as platforms such as Stocksy, MIDATA, Timesfree and Nursescan that have a focus on a particular sector. Instead of one platform that includes all these services, there is now an entire ecosystem of platforms.

Recently, the Platform Cooperativism Consortium (PCC) has been founded, a network that connects ten areas of activity: research, advocacy, education, design and experimentation, application development, solidarity, funding, legal consultancy, documentation and mapping and a speakers bureau. The consortium works on legal templates to be used by independent workers and coops, and is currently developing a mooc.

Scholz emphasized that there is a critique to this new term of platform cooperativism, because some think the very model has already failed many times. The reason why many platform coops fail, is because of their marketing and the challenge to break through the network effect, he stated. Sometimes they are not projecting values outwards, suffer from poor leadership, or have a lack of knowledge about the coop business model and its history. Lastly, there is the question of scaling up. In some sectors, there is a need to scale, but in many areas, projects can remain local.

The question is how these coops will work together and what this will bring as a movement. In the end, Scholz concluded, this is not about creating a coop, but about democracy that is reflected in all areas in our life.

MoneyLab #3: Trebor Scholz. Cooperatives and the Commons from network cultures on Vimeo.

An interesting proposal for a platform coop is commu.ne, a distributed ownership model for urban transport infrastructures. Arthur Röing Baer is a designer and writer, and founder of commu.ne.

Baer explained that because every passenger and taxi driver now carries a smartphone in their hands, it is now possible to completely re-design private and public transportation. Apps such as Uber show that taxi services can be controlled with less overhead and management, and Baer goes on to argue that there is no reason a cooperatively owned transportation infrastructure could not be designed in a similar way. According to Bear, there is a shift currently occurring in the transportation infrastructure which has caused three serious problems. First of all there is the exploitation of taxi drivers because of increased individual risk and information asymmetry. There is also the replacement of public transport, which offered a reliable infrastructure to everyone. While we agreed that we share responsibility for public mobility infrastructures, new logistical infrastructures are created and controlled by companies like Uber. In addition, automation is appropriating public transport infrastructures for example in London, metro drivers will soon be replaced by robots. Not to make the system more efficient, but to prevent drivers from going on costly strikes.

MoneyLab #3: Arthur Röing Baer. Cooperatives and the Commons from network cultures on Vimeo.

Baer wondered what an alternative system would look like that appropriates these infrastructures in a similar way. He stressed the fact that once a technology has been established, it gets harder and harder to intervene. Therefore he has started commu.ne, a scalable distribution model that is based on the blockchain. It offers both the drivers and passengers ownership checks through validating each other. Through sharing rides both passengers and drivers earn shares in the co-op and the proposal seamlessly merges both public and private infrastructure whilst adhering to the demands of workers who still need to make a profit. This type of distributed governance offers a new model for transportation that harnesses the same ambition as Uber but re-distributes capital, labor and ownership in a fundamentally pioneering way.

Another interesting example of a cooperatively owned community organisation is Hello IJburg, an online neighborhood platform developed by Michel Vogler. IJburg consists of artificial islands in the eastern part of Amsterdam, and has 50.000 inhabitants. All kind of local initiatives are being developed in the neighborhood, while often trying to find ways to cooperate with the municipality to get ideas implemented in policy.

Hello IJburg was created as a digital communication platform to connect with citizens but also with organizations and govs that are working with IJburg. By now, 4600 people have registered, while the software is developed together, there is data ownership and all the costs are shared. Other neighborhoods in the Netherlands have expressed their interest in creating a similar platform.

Vogler emphasized that he was very happy to choose platform cooperativism instead of platform capitalism. At the moment the platform is not making any profit, but if so, it will be shared with all the owners.

MoneyLab #3: Michel Vogler. Cooperatives and the Commons from network cultures on Vimeo.

Scalability and competition

The cooperatives and commons session ended with a conversation about scalability and competition. Is it always important for a coop to be able to be scaled up to have impact? Is it even possible to ever compete with huge platforms?

Trevor Scholz referred to the project Fairbnb that is currently being developed in Amsterdam. Although it is a good example, it could be hard to maintain, because this would be the kind of platform where one needs a network of cities to have a meaningful impact. In this case it makes sense to connect initiatives in different cities. But in other cases, like taxi services, a platform coop can be local.

He continued explaining that in Silicon Valley, 90% of the startups fail because they are offered 18 to 24 months time in which to return value to their financial investors. This means that the social value is already destroyed by the very model of venture capitalism, where founders have to maximize their profit to pay back their investors. Instead, local initiatives and platform coops will mostly develop much slower, but without the ‘artificial sugar infusion’ they have more possibilities to create social value, and to keep this value within the community.

MoneyLab #3: Cooperatives and the Commons. Q&A from network cultures on Vimeo.