Interview with Alex Foti and Trebor Scholz

by Cristina Ampatzidou and Ania Molenda

Amateur Cities for Moneylab #3 Failing Better

We spoke to Alex Foti and Trebor Scholz during Moneylab #3 – Failing Better? in two separate conversations, addressing a set of the same questions from two different perspectives. The final format of this interview as a conversation has a comparative purpose and should not be read as an actual record of a conversation.

CA: Can you say something about yourself? What is your background?

AF: My name is Alex Foti. I am an anti-precarity activist. In 2001 I co-organized the first May Day in Milan for and by precarious workers, which expanded into a network covering a vast number of EU cities. I was active in EuroMayDay until 2010, when the initiative stopped. Currently I am involved in movements addressing a radical notion of Europe. I am also writing a book on the precariat for the INC Theory on Demand series, with the working title ‘Great Recession 2008, Revolution 2011, Reaction 2016’. I think the precariat in Europe must mobilize to fend off national populism and fight for social emancipation via a European universal basic income and a European minimum wage. In particular, emulating the US union drive, we must fight for 15 euros an hour all across the eurozone, as this is the first cornerstone of equality.

Book cover ‘Uberworked and Underpaid: How Workers Are Disrupting the Digital Economy’ by Trebor Scholz

TS: I am a scholar-activist and professor of culture and media at the New School in New York City. In my latest book, ‘Uber-Worked and Underpaid: How Workers are Disrupting the Digital Economy’ (Polity, 2016), I developed an analysis of the challenges posed by digital labor and introduced the concept of platform co-operativism as a way of joining the peer-to-peer and co-op movements with online labor markets while insisting on communal ownership and democratic governance. My next book focuses on the prospects of the co-operative online economy. I have edited ‘Ours to Hack and to Own: Platform Cooperativism, a New Vision for the Future of Work and a Fairer Internet’ (with Nathan Schneider, OR Books, 2016) and ‘Digital Labor: The Internet as Playground and Factory’ (Routledge, 2013). In 2009, I started to convene the influential digital labor conferences at the New School. Today, I frequently present on the future of work, co-operative alternatives for the digital economy to media scholars, lawyers, activists, designers, developers, co-operatives, union leaders and policymakers worldwide. I am also a member of the Barcelona Advisory Council on Technological Sovereignty.

CA: Trebor, in your presentation you said that co-operatives are not about abolishing capitalism. How about the potential for a completely new system – are we prepared for something radically new?

TS: There have been various activist projects that lost steam because they did not offer any near-future alternatives that people could reach in their lifetime. I think what energizes people about platform co-ops is that they offer concrete and immediate action working in the direction of a fairer future. Cooperatives are not the silver bullet; they are not forcing capitalism to its knees, but they are creating better conditions for millions of people worldwide.

What I found very interesting in the panel on ‘Cooperatives and the Commons’ was the question of automation. I think that a coalition of rebel cities, unions, and co-ops should consider what role co-operative ownership of artificial intelligence (AI) could play in our future cities. Take Green Taxi Cooperative in Denver, for example, which is a platform co-op rooted in co-ownership and democratic governance. For Green Taxi to go driverless would be a very different proposition than for Uber, which would see its drivers lose their jobs. Green Taxi drivers would become collective owners of the AI.

CA: Alex, in your presentation you talked about the necessity of a revolution, taking over the European Central Bank and establishing a totally new system. How can we prepare for that?

AF: I have been thinking a lot about why we – the anti-globalization movement – lost the battle against global neoliberalism. Perhaps it’s because we were afraid of addressing social power, not as the authority over people, but as the ability to the change things collectively and contest state power. In Spain, for example, thanks to the force of the Indignados Movement and their way of transforming political dynamics, anti-globalization activists were able to create a new kind of politics with the ambition of surpassing the traditional left and going straight for power against the right. It was bold, and they succeeded in Barcelona and Madrid! Perhaps not irreversibly, but they managed to appeal to people’s needs in progressive terms. I think that’s fundamental today. We have to learn from them how to extend such pioneering experiments with social populism.

CA: Trebor, do you think that platform co-operativism can provide support for political awareness and engagement? Can we expect to see it on the rise in an era of total precarity and self-employment?

TS: In the US, the number of people actually working through platforms is minuscule; 0.5 per cent of workers indicate that they are working through an online intermediary, such as Uber or Task Rabbit, according to estimates by Harris and Krueger. But the business templates that these companies are establishing are going viral. We see what Bernard Stiegler called the uberization of society, where various companies fire workers, create a subsidiary, subcontract with that company and then hire back these workers as freelancers. It is in that sense that the predatory sharing economy contributed to the spread of low-wage jobs without benefits over the past decade.

AM: Is there still space for unions in this reality? Or as Emily Rosamond mentioned in her presentation: when the oppressor changes from the employer to the investor, the form of protection has to change from union to something else?

TS: Unions and co-ops are very different. Unions are outward-oriented and experienced when it comes to political work. Co-ops are all too often enclosed, sometimes not all that keen on talking to outsiders. They are not projecting their values outward sufficiently and may know less about international labor laws than unions in some instances. The whole job of a union is to know labor law, know the politicians and to advocate for workers.

Co-ops, on the other hand, are experts at running businesses. In this way, co-ops and unions can complement each other and reinvent themselves. There are various examples of platform co-ops in the US where unions support emerging co-operative platforms. Green Taxi Cooperative is a good example of such a union-co-op model.

CA: In between the idea of individualism and the co-ops, is there space for the emergence of a collective subjectivity?

AF: For more than a decade my activist work has revolved around constructing the subjectivity of the precariat. I consider the precarious generation an emergent social class, central in the accumulation of post-industrial, informational capitalism, yet peripheral in the political process. Youth unemployment is at about 60 per cent in Greece, 50 per cent in Spain and 40 per cent in Italy, and remains high at around 25 per cent in France and Belgium. Not even Scandinavia is immune, as a quarter of the Finnish youth and a fifth of young Swedes are out of work. In fact, the precariat has been steadily expanding since the crisis. According to various estimates, precarious and temporary workers now comprise 20 per cent of the labor force. Despite this fact, nobody is organizing temp workers or interns around their collective grievances and giving them a voice in the political process. What has been missing until today is a labor movement that addresses the social needs of the precariat. Everyone’s affected by job insecurity today, and most youngsters have lost faith in the economic system. Millennials, for example, don’t opt for private pension funds, because they don’t believe in the long-term future of capitalism; they consider it as irrational as to put their money in a casino. This calls for a return to the basic universal guarantees for everybody that was behind the old idea of social democracy, but this time making precarious recipients active partners in societal welfare rather than passive beneficiaries to be monitored and surveilled.

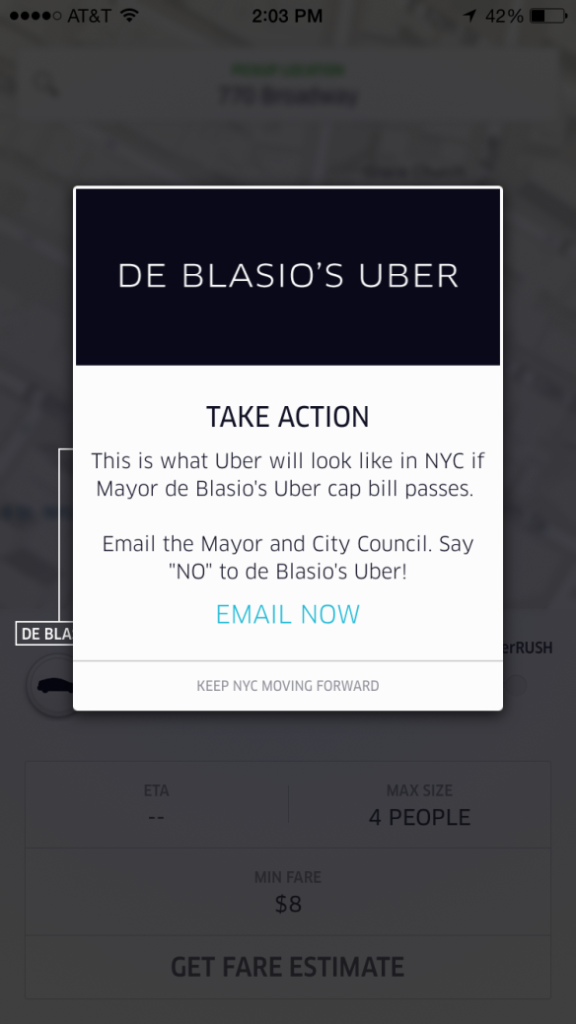

de Blasio’s Uber, source: https://techcrunch.com/2015/07/16/uber-launches-de-blasios-uber-feature-in-nyc-with-25-minute-wait-times/

TS: Companies such as Uber and Airbnb more frequently understand their users as a grassroots movement. Airbnb even hired a community manager whose main expertise is the study of religious sects and grassroots movements. These managers attempt to mobilize hosts in Amsterdam and New York so that they will advocate for deregulation in Airbnb’s favor. In Barcelona it wasn’t that easy, and the hosts turned around and protested against Airbnb. When NYC mayor Bill de Blasio merely wanted to limit the number of Uber cars in the city, the company built a feature into the app calling on users to ‘protest’ (by sending an email to the Mayor and City Council – ed.). Users/consumers were turned into advocates. Never before was it possible for a corporation to reach and mobilize its consumers on that scale and in real time.

CA: How, in that context, can we think of preventing collective constructions from becoming hijacked, turning exclusionary or oppressive?

AF: To me that’s where online democracy makes a difference. The emergent platforms for collective decision making have a possibility of controlling the delegates and voting down leaders who are prioritizing their personal interests over the collective ones. Podemos and the Five-Star Movement, even though I don’t really like the latter, have both been using digital platforms for such purposes, and it’s not inconceivable that we could come up with a constituent platform like this for a radical Europe. I am in favour of creating constituent acts that make the voice of the European people heard. That’s how a European demos can be created. Now we have nothing else in common except a currency that creates a virtual state of the eurozone. We must strive to achieve a political union.

AM: How would the identity of such union or a collective subject be created? How could we integrate diversity into it?

TS: If social justice is the goal, you need to start with exactly the kind of diversity you want to end up with. So if you want to have diversity on your platform, your team needs to be diverse from the very beginning.

AF: To address various subjectivities and federate them into a populist whole my code would be: ‘pink, black, green’. Pink stands for queers and feminists – even though they’re two different constituencies, they both fight for gender rights. Black stands for cyber rights, freedom of expression and freedom of public assembly. Green of course for climate justice. These three things comprise myriad subjectivities. The point is to federate them into a political program that I would call left or social populism.

AM: Is it also true for co-operatives that identity constructed around specific needs of certain groups of people gives a stronger incentive to organize?

TS: If I understand your question correctly, you are asking about the motivations that historically led to the formation of co-ops and unions. You could start thinking about so-called piracy, for example. British sailors were so violently maltreated by their rulers that their choice came down to death in servitude or mutiny, escape and a life of relative dignity. There are parallels to the founding story of co-operatives that leads us back to Rochdale, England in the 1840s; that geographic region and time period was also the birthplace of unions. The Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers was a response to a very particular need. The founding members were starving and figured that buying oatmeal, milk, and bread and butter in bulk was cheaper.

In today’s US, I see opportunities for platform co-ops in specific sectors. There are genuine needs in the home health care sector, and hundreds of thousands of people are coming out of prison every year. They struggle to get well-paying jobs, and self-organizing in co-ops could really help them.

CA: What do you think should be the approach towards a radical change? Should we start from a big vision of where we want to get to, or should we define practical steps first?

AF: I think it’s the moment of grand movements. The anti-globalization movement had a big international vision, but at the same time thought in simplistic, oppositional terms, with global capitalism on one side and us on the other. So, if we defeated global capitalism, we would reach solidarity between North and South, and a society based on fair exchange. That was fucking naïve! Capitalism doesn’t work that way; it is a historical formation, and we are all entangled in it. Even ISIS has a capitalist aspect. They sell oil to fund their murderous project and are therefore a part of the market. What we have to do is to organize ourselves at all levels against the mutation of neoliberalism into national populism with Trump and Le Pen. This includes exerting cultural counter-hegemony, constructing a European revolutionary movement and a syndicate of the precariat, in alliance with our American, Japanese, Canadian and Korean sisters and brothers. Looking at the humiliation of liberalism and resurgence of xenophobia all across Europe, I think we have to start building a European militia that fights against the racist threat. It might sound macho and militaristic, but let’s at least be ready for self-defense – for the times are ominous.

CA: Trebor, what would you see as a fruitful way?

TS: Well, I think the #BuyTwitter campaign[1] is wonderful because it’s so bold that it inspires people. With small steps you can’t inspire people that easily. I think it’s very energizing to listen to grand visions, but what I would caution against is an attitude that suggests that until all of this has happened, we can’t do anything. In the US, people supporting platform co-operativism are usually in their mid-20s, early-30s, interested in technology and looking for jobs. They see platform co-ops as something ethical that can actually financially sustain them.

#WeAreTwitter from Tristan Copley Smith on Vimeo.

And this is something to which the Free Software movement has not paid enough attention. Richard Stallman is not opposed to people making money from free software, but in reality there have not been very many free software co-operatives. Usually free-software programmers have a day job where they have to neglect their values to then do the cool stuff at night. It’s interesting to see how that can be changed. It’s crucial to have these imaginaries – of a global commons, a post-capitalist, post-work society – but the stepping-stones are equally important. So, while I’m all for the revolution, let’s not forget that even Wikipedians and free-software programmers have to feed their kids.

This interview with Alex Foti and Trebor Scholz is part of the Amateur Cities collaboration with the Institute of Network Cultures for Moneylab #3 – Failing Better.

[1] Recommended reading: ‘Here’s my plan to save Twitter: let’s buy it’ by Nathan Schneider, The Guardian