Filter mainstream, which eventually applies to monetized human experiences, calls for the imagination to design new narratives for being together. Some commodified experiences wear out faster than others, and some expand to become their different (perhaps better?) version. Clubbing too, is a part of experience economy, where feelings of boredom started to emerge (when exactly? has not been specified in the history yet). At the same time, clubbing currently seems to be the richest context for experimentation. Due to my personal perplexity, and inability to guesstimate the direction in which these experiments are going, I digitally approached the people behind the CryptoRave project, as an attempt to demystify this foggy cloud.

Filter mainstream, which eventually applies to monetized human experiences, calls for the imagination to design new narratives for being together. Some commodified experiences wear out faster than others, and some expand to become their different (perhaps better?) version. Clubbing too, is a part of experience economy, where feelings of boredom started to emerge (when exactly? has not been specified in the history yet). At the same time, clubbing currently seems to be the richest context for experimentation. Due to my personal perplexity, and inability to guesstimate the direction in which these experiments are going, I digitally approached the people behind the CryptoRave project, as an attempt to demystify this foggy cloud.

CHARACTERS

M = Maisa

O = Omsk Social Club

B = Bitnik

M: First of all, why is there a fireball dancing the zooming-in-and-out moves, first thing when one enters the website?

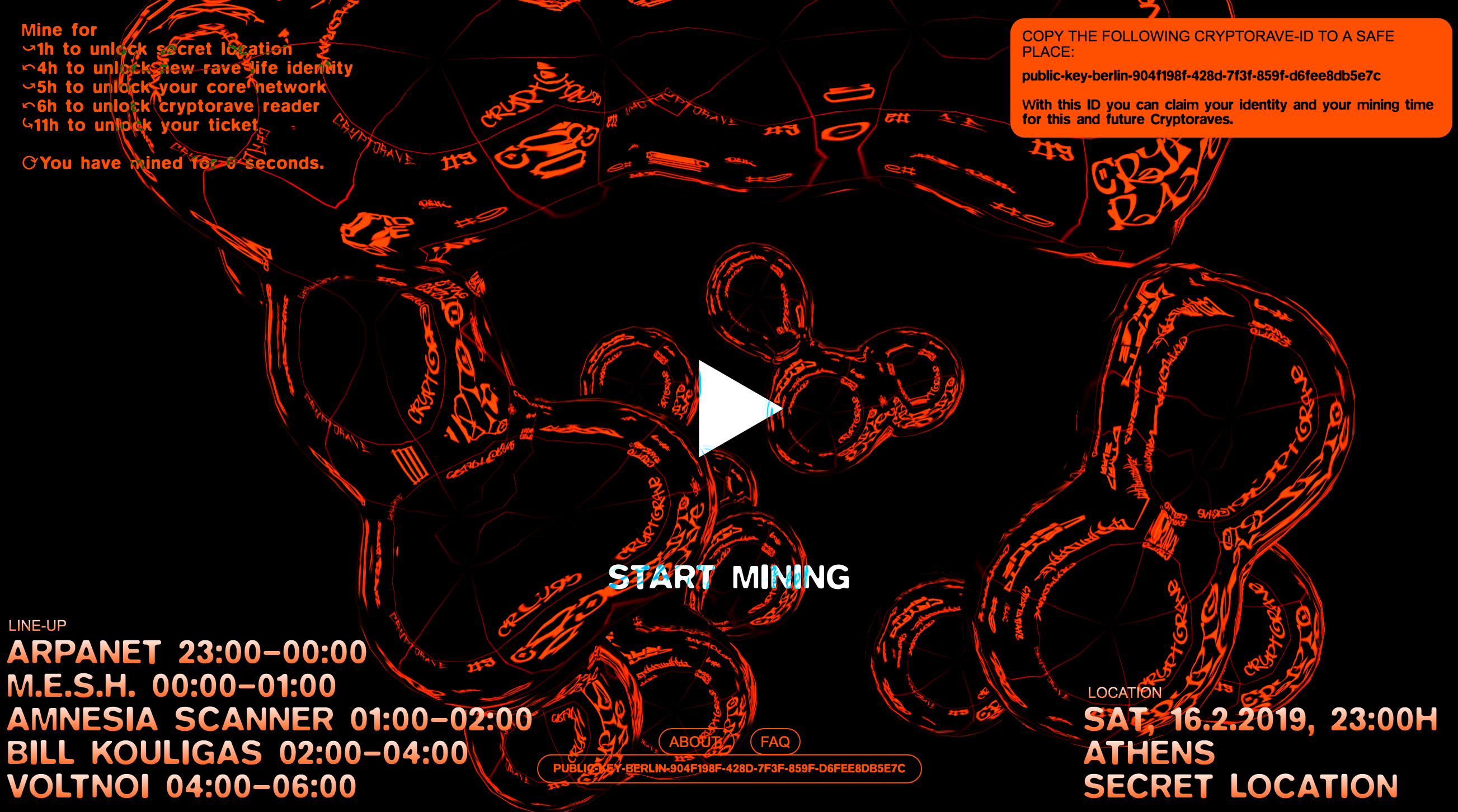

B: It was part of the concept for the Cryptorave series to create a specific website embodiment for each Cryptorave, taylored to the location and framing of each event.

We worked on the website with the amazing designers Knoth-Renner to come up with a different visual for each event. The fireball was the visual for Cryptorave #10 at the House of Electronic Arts Basel in March 2019. The dancing fireball in a way represents the accelerated disintegration of things we thought of as given, of safety and security; how many of our trusted truths are rapidly disintegrating. Our fireball simultaneously has raging and chaotic fire-insides, while at the same time it is oddly contained and frozen in time.

M: Could you briefly describe what CryptoRave is about and what is its relation to blockchain?

O: Well from our side it was an idea, that can be broken down into three parts first it’s firstly a traditional rave – that nostalgic dance floor, crowded bathroom, grinning faces and late nights that is initiated through a URL rather than flyposting or flyers or ringing a number after 22.00 to get the rave location. The second part of the cryptorave is much more focused on the technological ideas, politics, beliefs and their opposing forces which surround the blockchain hype, crypto circuits and decentralized hive minds – how we delivered the latter side of the Rave is through Real Game Play (RGP), a type of role-playing reality that Omsk coined in around 2016. To break it down further, each rave goer gains a new identity with their mined ticket from the url which also includes the location, line-up etc. This new identity is theirs for the evening. In order to play it, they must naturally research it, body it and enjoy/suffer in it… We also run workshops before the Rave for people to gain further access to this element. The third part is the technological code – the RaveEnabler which was created by bitniks and KNOTH and RENNER, which allows the rave to be financed by a Monero mining pool. Meaning your computer has to mine 11hrs worth of CPU, to release all the elements you require for the rave, such as your identity or crypto reader. You are by default supporting the cryptorave Monero pool with your CPU. Hence you’re paying via your desktop computing monero hashes. But the real beauty of such a piece is that in essence, you can have all these elements, but whatever happens on the night happens – no one afterall can direct a decentralized party 🙂

B: Cryptoraves are utopian experiments with blockchain technology, cryptocurrencies and DAO to support and power a subculture. Cryptoraves open a thinking space in which sub-cultural networks can examine blockchain technology as a means to structure and put value into networks. This is achieved both through actual mining of cryptocurrency by participants and through a layer of Real Game Play (RGP).

To attend a Cryptorave you need to mine the cryptocurrency Monero (XMR) to receive your entry pass. By joining their computing power together, the community collectively generates value to fund the Cryptorave machine and enable the autonomous dance party experience. The collectively generated value aims to ensure the basic existence of the network and to provide an amount of security and privacy. At the core of this experiment is the RaveEnabler, a website with an embedded Monero (XMR) miner. Just like other miners, it uses the participants computing power to validate transactions within the Monero network.The Cryptorave took form as a collaboration between the two artists groups, Omsk Social Club and !Mediengruppe Bitnik. In the Cryptorave, the two artistic practices become intertwined, leading to the idea of the RaveEnabler and the Cryptorave as a utopian gesture to examine whether blockchain technology and cryptocurrencies can be used to create sustainable sub-cultural networks. The RGP connects the club space with the gallery and the crypto-scene. The RaveEnabler is the technology at the core of this experiment. The RaveEnabler website crosses over into the IRL space of the venue. The art inserts are used to disrupt the seamless flow of the rave experience — this creates glitches, gaps and irritations which create a thinking space.

M: Considering the fact that you are two collectives behind the project, I’m curious to know what clicked into bringing you to collaborate?

O: The curator Sakrowski from panke.gallery (Berlin) introduced us to !Mediengruppe bitniks and it seemed like a good coupling to take the cryptorave public with. By saying that, I think it’s important to say that we did not create the cryptorave – it came from close, but outside sources.

M: How do you choose cities and locations/venues for the raves? Is the decision lead by the amount of people that mine/come (so for the sake of hosting everybody); or do you select venues based on their status/reputation; or are there some other reasons which completely disagree with my assumptions?

O: Well, the cities were based on invitations from hosts, people who wanted to have the cryptorave concept as a part of their program or event.

B: All the Cryptoraves we produced in the past year were by invitation of a host institution. We produced a Cryptorave last October with The Influencers festival in Barcelona for example, where we were interested in exploring virtual relocations as a glitch: Through Adam Harvey’s project Skylift, we used WiFi geolocation spoofing devices to virtually relocate participants of the rave at the warehouse space in Barcelona to the pool at Peter Thiels’s holiday home near Makena Beach on Maui, Hawaii. Participants received text messages on their phones welcoming them to Peter Thiels pool party:

Welcome to the Faraday cage. Only we can see you now.

7150 Makena Road, Hawaii.

Welcome to the only party to ever happen at Peter Thiel’s pool.

Peter Thiel is not here right now. But make yourself at home.

All mobile communication that participants sent out during Cryptorave #7 in Barcelona, was location tagged as being from Hawaii. This led to some funny confusions, especially after the party was closed down by the police and everyone needed to call a Taxi. People who ordered through geo-location-based taxi apps, had to walk a few blocks to reset their geo-locations. Otherwise they would have ordered the taxis to Hawaii.

At Cryptorave #8 at transmediale Berlin, participants were relocated to the Berghain club in Berlin. The first 200 participants received a Cryptorave Kit containing a water bottle, face mask, glow stick, glove, Cryptorave stickers, webcam covers, a cryptorave lanyard, security vest and a link to the online Cryptorave reader.

In each new Cryptorave instance, we added a number of characters, specific to the conceptual narrative and to the location. Local crypto-communities and art scenes are written into the play, and specific attributes of the location are added. So basically, every new Cryptorave location has to be intriguiging and interesting and allow us to further develop the concept.

M: How strict are you with the Real Game Play-mindset? Perhaps a better way to answer my curiosity would be: Are visitors instructed to pro-actively play throughout the whole rave?

O: Identity is always in flux, be it a conscious one or role-played one; and a rave is always more than just a rave. A rave, by definition, has always had the potential of being absurd, naturally due to the heavily altered states in which most of its populations ground themselves in. It is also a place where time stops and personalities are unleashed for better or worse. Flickering thoughts and philosophical muses are on everyone’s lips and chewed up tongues, inside a rave space. Bodies and minds just run. People connect to unknown others either on the dancefloor, memetically matching tempos and limbs, or in toilet lines, or sitting on a curb crashing roll-ups. Bodies act as if they had known each other for years on the dance floor, and perhaps they have. Possession is always part of the Rave: who or what has possessed these rave users is questionable and blurred; is it drugs? Other nostalgic spirits? Other characters? Or their own minds?

There is another unusual thing that happens inside these places, and that are the states of extreme euphoria and extreme trauma that are reached by its users. What’s even more exceptional is that they are met with the same terms of negotiation. Neither is seen to be more or less acceptable by the community. You are always seen to be working something out, even if it is vehement sadness. It is accepted as such, no matter how many people think it to be an unhealthy route of action. Inside this life, cuts bleed and scar… as do kisses. This place that credits absolute emotion is the hardest and safest space Omsk ever found ourselves to be inside. The Rave structure has informed our practice much more than traditional role-playing has, but it is not wholly different in its collective narratives, chimaera illusion and off-world structures. Inside a rave, you know you can be anyone, but you can never get away from who you are completely. You will always let something bleed into your experience from what you left behind and vice versa.

M: I totally agree with that. But with Real Game Play rules I wonder what is the level of participation. How well do visitors play along? Are they confused? Or is invitation-mining already a satisfactory experience?

B: The levels of participation vary, of course. There are participants who are masters at this RGP form of participation, and hugely enjoy the experience of the Cryptoraves. But also for the less enthusiastic participants, the experience of sitting alone with a computer and waiting for it to complete the mining process, unlock the character, the Cryptorave reader, the secret place etc. functions as an entry point into the RGP. A bit like falling into a rabbit hole. The mining process through RaveEnabler creates a totally different connection with the event. Compared to the more common process of buying a ticket, people form a much stronger connection to the event beforehand. People tell us they highly enjoy the excitement of the preparation and the weird experience of having their computer, their very personal device mine away and work and work, and they are not sure what the computer is doing exactly. For many participants it is their first experience with crypto-mining. While waiting for the mining process to conclude, they dive into the Cryptorave reader, research their character, find out what the hell blockchain is. Bringing people into the thinking space around blockchain and cryptocurrencies was one of the main motivations for this work. We see these new technologies opening up utopian spaces. But at the same time, most of the people adopting these spaces are in it for the money, not for creating new connections or utopian thinking.

O: In our RGP’s we don’t believe you can ever get rid of yourself and in trying to do so, you are committing yourself to a self-induced state of spiritual anorexia. This disorder is commonly found in the “real world”. We are constantly told one must reduce and ‘self-sculpture’ your Life, not for yourself – so we deny our bodies the possibility of experimentation with another us, just in order to concentrate on getting that silky smooth surface of the self-perfected Self. If people choose to fully commit to the experince, they will gain something wholly different to not doing so in the same way they might not commit. But the person they spend the whole night with does. It still shakes the foundations of what is a known reality and what is not. This is for us the most interesting space in the spectrum of experince and experimentation. In a way, the cryptorave is the most messy piece we have ever done but people do seem to enjoy it and others get something out of it, while others get nothing, just like any artwork: it is not for all, but everyone can show up, figuratively speaking, and experience it.

M: Yes, true. Speaking of mining and waiting, why does CPU donation last for 11 hours?

B: We experimented with the times and 11 hours turned out to be exactly the right amount of time to get people involved without asking them to commit too much time.

M: Let’s talk about terminology. Visitors doesn’t sound charming at all, is there a term you use amongst each other, which refers to the attendees?

B: We don’t use the term visitors, we use the term participants. We provide the tools for the Cryptoraves, but the event itself is collectively produced by the participants.

O: Ravers, Guests, Players, Friends…

M: Do Visitors, Ravers, Guests, Players, Friends question the CPU donation or they don’t care when the only aim is to party?

O: Luckily yes, people question it, mostly the environmental effect – if people didn’t question the piece it would not be working… it’s not about giving answers for us or how to fix the world-style manuals – it’s about asking questions that we don’t know the answers to, and thinking through them collectively. This is also why we have all shades of political characters and different sets of knowledge attached to the mined identities. We need the whole set of opinions rather than just a leftists echo chamber in order to pursue this narrative with any objectivity.

B: Many of the particants have told us that making their computer work to get into the party, instead of just being able to buy a ticket, very much changed their attitude towards the event from being a consumer to becoming a part of the event and realizing that they are helping to produce the event. This is very important and one of the main points: Using technology to change the way we relate to a community or a collective experience. Getting people involved in a more active way.

M: YES! That sounds like a way to transform passive participation into a pro-active/”responsible” one. I’d like to move on to some less practical questions. Did you start the project off as blockchain experts, or was it a learning curve depending on the process?

B: We have actually been working within these spaces for a number of years. Our first encounter with the crypto spaces was in 2013/2014 working on our piece Random Darknet Shopper. Random Darknet Shopper was an online shopping bot that went shopping in the Darknet, choosing and purchasing one item per week for 12 weeks and having the items sent directly to the exhibition space. The work raised questions around accountability of automated algorithms and bots, but also around anonymity and trust cultures within the Darknets.

Bitcoin was the leading cryptocurrency at the time and the only currency accepted in the Darknet markets. It not only guaranteed ease of use through its digitality, but also a certain level of trust through the blockchain. We had come across the crypto-space in the past, but this was the first time we did a deeper research into crypto-spaces with it’s diverse sub-spaces, niches, groups and beliefs. The future for crypto-spaces seemed wide open and Bitcoin was still used as a currency. Places like the Institute of Cryptoanarchy at Paralelní Polis in Prague opened up: They only accepted payments in Bitcoins, at the bar, for events and workshops. Since then, the crypto-spaces and the discussions around blockchains and DAOs have been fast-paced and ever-changing. So, continuing our research through the Cryptoraves has been an interesting process of constant learning.

M: Why did you choose the clubbing context to be the source for blockchain input? What does clubbing mean to you?

B: We think clubbing and raving are excellent contexts to experiment with different forms of producing culture, consuming culture, funding culture, forming networks. Dance culture is very fundamental to any cultural scene and also very specific to every local place, with its own codes and customs. Dance events are a fundamental cultural technique and people intuitively understand how the events work. You don’t need to explain it. So, we can take dance events and ever so slightly change the rules and the settings. The result, the glitched event is then open for everyone to experience.

O: A rave was always a place where you were somewhere, not nowhere, and nobody cared where….Growing up across Glasgow, Manchester, Leeds and later Berlin, we were always drawn to the construct of a rave, because it seemed to us that it is one of the only places left in contemporary society where a body can still be awake and offline. We spent some many hours inside these machines that eventually, it just seemed obvious. The Rave gave us the perfect inlet for immersion to an alternative world, without telling everyone hey we are going to play inside a new world. That seemed abstract and reductionist, as we wanted to work with the worlds as beta, or test sites for our own world. Our first public large scale piece was a rave in 2017 in Zurich called “PLAY RAVE” it had over 400 Live identities and was set just outside of the city. To find the location, you had to follow the Limmat river out of the city, under a motorway bypass and into the first alpine forest clearing. It was set-up as an illegal rave supported by Kashev, a local Zurich crew. It ran for 6 hours starting at midnight. Players at random were given identities after they applied for them via an open call email. The characters had been constructed from looking at and speaking to four different generations of crews, promoters, DJs, producers, dancers, and cult figures in Zurich that had put on illegal raves in the city-the earliest in the 1980s.

The identities weren’t constructed from facts, but emotions; people were interviewed based on their lives, memories, crushes and pains. The person interviewed remained anonymous to the player who received their capsule of thought. Names were changed but attitudes, politics and nostalgic events stayed the same. Remixed into common political phenomena, we birthed 400 people who played, danced, roamed in alternative states and question what was authentically real and what was not. It was the latter that gave us hope. We never aimed to create seamless characters, polished defined bodies acting out directions. We wanted to bleed, we wanted to shake peoples connection to the architecture of the rational. This was a piece of participatory role-playing co-immersion, and we knew right at the start we were not writing LARPS as such. Our language was different, so was our incentives for play; and hence, we called our spaces Real Game Plays. They sat inside the framework of Art – this is our landscape, not LARP. Although many would argue we create LARPs, we can see the commonality but LARP is its own defined ever-growing subculture, and we are not part of it.

M: Lovely. I guess it is hard for self-crafted frameworks to survive un-labeled as something already existing. I’d like to know what are your thoughts on current experience of clubbing; in terms of how the night reaches its climax and everybody goes home – so, the narrative?

O: Ha, not really sure how to answer, this is so subjective…but from a personal space you never just go home, the experience is there, it bleeds out into your life, your body, your mind – whether that’s with a hangover, or sore limbs, or waking up with someone close. Experience culture is one thing, but a subculture is another: if you’re part of these spaces, they are your life…Is this the crux of the question maybe? The fact that clubbing culture has been steadily pushed into the mainstream, and in effect has lost its emotive sentiment – maybe?

M: Yes, something along those lines.

O: Rave has become more popular in its sound, aesthetics and movement, one can easily find its signature style in fashion, graphics, and art of today’s contemporary world. The art world is even writing reviews about it…take Jenny Schlenzka’s Frieze article in which she reviews Berghain. I think the ritual is a part of it, and you can’t learn a ritual in just one night. But, you can experince it. Right now it seems like we need ritual communal action, and perhaps a club allows for that, in some strange fast-food spiritual way. Second-order cybernetics states that societies and communities are built up of systems and social-ecological rituals that perform positive and negative feedback loops on a recursive basis, depending on a need, rather than solely tradition. Which may be the answer as to why we see now a rave revival happening in recent years: maybe we need it.

B: Clubbing is very much tied in to local cultures and ways of organizing. This is what makes it interesting to tap into. What time do people go to the club? How do they prepare for the night out? What is regarded as the climax etc. It’s all very different depending on where you are, what scene you belong to. What always remains is the collective experience of creating something together. This is maybe more intense at a crypto-rave, because people become more aware of their part in it through the slightly changed setting.

M: That wraps some more material to think about. But let’s say that there are two categories to place crypto-raves in: statement of today + vision of future. Where would you place your project?

O: in the middle that + sign, its both a statement and a hypersituational promise 🙂

B: Hopefully it is both. Every new Cryptorave reflects on the today, while at the same time imagining a more diverse future.

M: Is there a limit to the continuation of the project, or do you see yourself just continuing with the organisation? How do you see it evolve in, say 3-7 years?

B: After having run a series of crypto-raves over the past year, we are working on amalgamating our experiences. We want to open-source the concept and the RaveEnabler software, so that others can run crypto-raves as well. There has been a lot of interest from various venues and event producers in adopting the RaveEnabler for their events.

O: We are stepping back from the crypto-rave series, it was an experiment that was test-bedded in the arts but we are not experts in decentralized rave systems, so hopefully those who are will continue with it…On that note, we never saw the crypto-rave as ours – it’s open to anyone. You can never claim ownership of such a system, and if you do it will deny you – as any good egregore should.

M: How well said. Egregore is a word to keep an eye on.. . To conclude this trajectory of in-the-club thinking, my last question is: what is the core mission of CryptoRave?

B: To create a collective thinking space around possible uses of blockchain, cryptocurrencies, anonymity, obfuscation, collective organizing, community stakes to create and fuel subcultures, DAOs. This happens through the real-time, slightly glitched experience of a dance night, where I am released from being myself (if I want this) and can experience the rave through a different identity. But first, with the help of my computer (and usually alone) I need to burrow myself through the crypto-layers leading to the event. The 11h alone-time set a stark contrast to the intense collective experience of the rave. A heightened experience of how we now are in the world: Alone with our devices and together at events in confusingly quick succession.

CryptoRaves are designed to bring people into the thinking spaces around blockchain and crypto. We believe that the ways of thinking (libertarian, anarchist, utopian, authoritarian) will determine much of the thinking around technological change in the future. We believe it is important to bring more diverse views, expectations, ideas, imaginations into this space.