Image from Piek!

Report from ‘blockchain for social good‘ workshop at European Commission in June 2016

On 21st June the Digital Single Market Council (a division of EU parliament) invited the full cavalry of blockchain and bitcoin advocates to Brussels to discuss the future of distributed ledger technology (DLT). The room was packed full of entrepreneurs, business people and middle management consultants all demonstrating an interest into blockchain technology, and how they can get to grips with the new technology to turn blockchain into a ‘technology for social good’.

Image by Alexandre Pólvora

I was immediately surprised by the imperative taken by EU council to host such an event as it shows that blockchain advocates have clearly kicked up enough of a storm to reach the agenda of European Parliament. The attempts to professionalize blockchain technology and begin to strategically plan its implementation into European policy were unfortunately slightly tarnished by the calamitous DAO ether hack that had occurred 2 days before. Although most speakers were forced to address the DAO scandal and offer short term practical solutions (rolling back Ethereum platform to reverse and cancel previous transactions) nobody was keen to say how badly this ‘bug in the code’ had effected the political values and social credibility of DLT. The powerful and enchanting rhetoric of blockchain took a severe tumble after Vitalik called for a cease of trading to help stop the ether hack, turning the bright prospect of a de-centralized autonomous market into a gloomy centralized dictatorship.

Although DAOs and Ethereum are just one part of a much wider horizon of DLT potential, we should not forget that a lot of the de-centralized socialist storytelling involves smart contracts and DAO technology cutting out intermediaries to empower collective citizen governance. Much of this rhetoric has repeatedly been told by Ethereum ambassadors such as Vinay Gupta and Primavera de Filippi (see Promises of the Blockchain). So it was somewhat contradictory to hear De Filippi discuss the potential for de-centralized autonomous organisations to contest top down power structures in none other but European Parliament in Brussels – probably the most visible examples of centralized power in the western world. While De Filippi opened the morning session discussing the potential for DAOs and the implications of smart contract legislation, many of the audience grappled with some unfamiliar concepts and terms in attempt to convert this new wave of disruptive tech into their business logistics. For many there, this event was an opportunity to gain and understanding of blockchain and apply de-centralized technology into their long term business prospects. There were advocates from both sides of the blockchain debate, representatives from Visa, Mastercard and IBM sat alongside Bitcoin evangelists such as Pindar Wong from Scaling Bitcoin and Amin Rafiee from Bitnation.

Although DAOs and Ethereum are just one part of a much wider horizon of DLT potential, we should not forget that a lot of the de-centralized socialist storytelling involves smart contracts and DAO technology cutting out intermediaries to empower collective citizen governance. Much of this rhetoric has repeatedly been told by Ethereum ambassadors such as Vinay Gupta and Primavera de Filippi (see Promises of the Blockchain). So it was somewhat contradictory to hear De Filippi discuss the potential for de-centralized autonomous organisations to contest top down power structures in none other but European Parliament in Brussels – probably the most visible examples of centralized power in the western world. While De Filippi opened the morning session discussing the potential for DAOs and the implications of smart contract legislation, many of the audience grappled with some unfamiliar concepts and terms in attempt to convert this new wave of disruptive tech into their business logistics. For many there, this event was an opportunity to gain and understanding of blockchain and apply de-centralized technology into their long term business prospects. There were advocates from both sides of the blockchain debate, representatives from Visa, Mastercard and IBM sat alongside Bitcoin evangelists such as Pindar Wong from Scaling Bitcoin and Amin Rafiee from Bitnation.

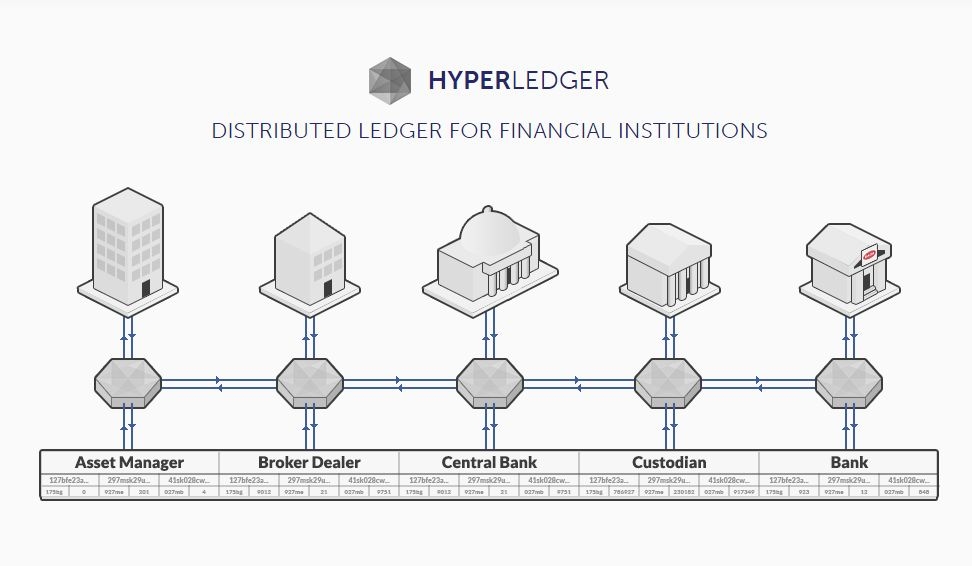

Matthew Golby-Kirk from IBM presented the Hyperledger a collaborative effort to offer commercial or private scalable versions of blockchain, where p2p values manifest into business-to-business logistics. There were very few examples of ‘social good’, unless you can interpret social good as lowering logistic costs and increasing profits. Jessie Baker offered some ‘real world solutions’ rather than just back-end technical fixes for big companies, in the form of provenance.org, where products are registered and tracked using blockchain to ensure an equitable supply chain. This is still in early development but has successfully been applied in the fishing industry to ensure the catch of the day has been caught legally. In the few examples of blockchain technology that were presented during the workshop many seemed to enforce existing regulatory structures with networked computing, such as EU fishing regulations (in the case of provenance.org). It was interesting to observe how blockchain technology was maturing into commercial business contexts to actually enforce existing regulatory frameworks rather than create opportunities for self-organized unregulated social structures. Generally, the implementation of blockchain in businesses that are capable of adopting the technology is geared towards replacing middle management and intermediaries with autonomous, de-centralized code. Take for example, the research into DLT by Catherine Mulligan at Imperial College, who have developed a program that uses blockchain to verify qualifications listed on job applications and resumes. Rather than becoming a tool for self-organised community empowerment, DLTs are quickly being incorporated into verification software and transaction based systems. Companies and businesses seem to be the first to seize the benefits of a digital public ledger as an administrative tool for legitimising digital exchange and managing information with de-centralized infrastructures.

Image by Shawna-X

Fortunately, there were two presentations in the afternoon that questioned the commercial application of blockchain technology and even offered some more inspiring visions of DLTs in social projects. Brett Scott (The Heretics Guide to Global Finance) wanted to re-frame the interpretation of the ‘blockchain for social good’ title and move towards a discussion on financial inclusion and network monopolies. Brett asked how, if possible, can DLT provide alternative expressions of value that can improve financial inclusion rather than streamline the technical infrastructures of existing financial corporations. Although many of the businesses present seem keen to break up platform monopolies (Amazon, Google, etc.), there seems to be little planning or interest into how blockchain and decentralized technologies can actively re-distribute wealth for the long term, rather just pan out as another disruptive technology in the competition for market dominance.

It was also fascinating to hear more from Dyne.org whose EU funded research into re-designing democracy has led to technical prototypes that are being used in political parties and communities across Europe. Iceland’s complimentary currency to incentivize political engagement and participatory accounting for the council of Reykjavik is a promising example of de-centralized technology being used for non-commercial citizen based incentives. The outcome of Dyne’s research project is wide and varied and demonstrates attempts to develop alternative expressions of value with DLTs that support communities and non-commercial infrastructures.

Instead of dealing with the underlying concerns and original opportunities associated with blockchain, the workshop predominantly consisted of endless examples of blockchain applications and business prototypes that strive to become new players in the de-centralized tech market. Interesting confrontations between Jakob von Weizsäcker (member of the European Parliament) and Bitcoin fanatics provided some light entertainment, with Von Weizsäcker concluding, somewhat defensively, ‘you cannot regulate what you don’t understand’.

To help EU Digital Social Innovation Board understand blockchain technology further they have allocated 2 billion EUR over the next 10 years for research and development. By that time I imagine distributed ledger technology will be firmly cemented into the global industry as the potential for networked transaction systems is appropriately fitted to serve the interests of commercial trade. The inability to imagine alternative use cases for p2p distributed networks to enable greater financial inclusion, citizen empowerment or civil organization will lead to the inevitable commercialization and privatization of blockchain, and bankers will fondly remember Bitcoin as the greatest gift the hackers ever made.

Full report published here and slides from the event can be downloaded here.