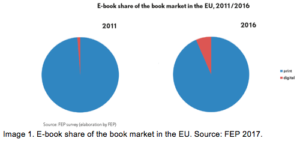

Book publishing is one of the largest creative industries in Europe, deeply rooted in European history, thinking, and identity and in the different cultures, languages, and national markets across the continent. The European cultural industry of publishing nowadays has a still strong market value worldwide (FEP 2017). However, while disruptive technological developments have led to intensive innovation using the affordances of digital technology in other cultural areas such as the music and film industry, publishing is still rather conservative, and the innovation of formats and revenue models seems to have come to a halt after the takeover by major media monopolies of a large market share in the digital publishing industries. Professionals in the publishing industry agree that there is no turning back when it comes to incorporating digital technology in the business of book making, but that such technologies have not brought the change that was hoped for. This is reflected in the available data on the publishing market; e-book shares are still but a fraction of the total market value in book publishing in the EU (FEP 2017) (see Image 1).

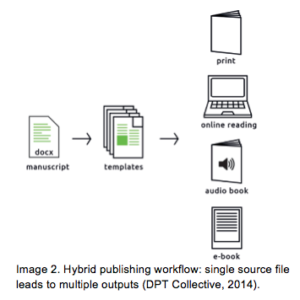

This is mostly due to a low value attached to digital products, not only on the side of the public, but also on the production and publishing side. Most publishers offer some kind of electronic publication in addition to their range of print books, but this mostly concerns a one-on-one digitised version of the paper book. Such a conventional approach to digital products cannot be expected to lead to a sustainable market share for e-books or other digital outputs in the book sector. A consensus in expectations is that print and electronic publishing will continue to coexist in the future and that there will be no such thing as the end of the paper book. To fully benefit from such coexistence, however, investments must be made to develop the electronic part of the spectrum accordingly, and as such make it more than just an appendix to print. Digital outputs should be incorporated from the start of the publishing workflow; working towards multiple outputs from a single source file is the first step towards such a balanced hybrid publishing practice (see Image 2).

This is mostly due to a low value attached to digital products, not only on the side of the public, but also on the production and publishing side. Most publishers offer some kind of electronic publication in addition to their range of print books, but this mostly concerns a one-on-one digitised version of the paper book. Such a conventional approach to digital products cannot be expected to lead to a sustainable market share for e-books or other digital outputs in the book sector. A consensus in expectations is that print and electronic publishing will continue to coexist in the future and that there will be no such thing as the end of the paper book. To fully benefit from such coexistence, however, investments must be made to develop the electronic part of the spectrum accordingly, and as such make it more than just an appendix to print. Digital outputs should be incorporated from the start of the publishing workflow; working towards multiple outputs from a single source file is the first step towards such a balanced hybrid publishing practice (see Image 2).

This need for a hybrid publishing workflow acts as the basis of the innovative aspects of EXPUBLIQUA. A truly hybrid publishing workflow, where digital publications are fully integrated into the publications range, calls for a thorough adaptation of strategies and work processes, based on different skill sets that have to be combined within traditional roles in the publishing process (DPT Collective 2014). An editor will have to get familiar with techniques of design, a designer has to gain skills in digital development, and so on. Hybrid publishing in this sense has been a key focal point in two large research projects conducted by the INC, in collaboration with some of the partnering consortium members.

In the Digital Publishing Toolkit project (funded by the national practical research fund of the Netherlands, SIA-RAAK, 2012-2014), an open source toolkit and accompanying ‘how-to’ for making EPUBs was developed. Some publishers have implemented the newly developed hybrid workflow in their businesses, but a new workflow doesn’t automatically stimulate new formats or encourage creative exploration of the possibilities that digital technology offers. To galvanise innovation and the ability to innovate within agile teams where members share different skill sets, it is necessary to develop the expertise for such hybrid publishing practices further and to diversify the output range of the publication products. The two of course are connected: new outputs should come out the imaginaries of the experienced professional and not be concocted separately from the market reality. To this end we initiated the Top-up project (funded by SIA-RAAK, 2016-2017) which allowed the INC to investigate current wishes and challenges in the field regarding such skills for innovation, and provided for two meetings to bring together the EXPUBLIQUA consortium and develop this proposal.

In the Digital Publishing Toolkit project and in the preparatory EXPUBLIQUA consortium meetings, the experienced difficulties in developing an innovative publishing practice under circumstances of ever-tightening revenues and budgets cuts for cultural experimentation have emerged again and again. This is not only to be blamed on the conservative character of the publishing field, nor on the precarious state of publishers and their collaborators (authors, designers, editors, programmers), but has to do with a trend towards centralisation and standardisation on the side of the available technology as well. The EU agenda as for example stated by the Directorate General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology or ‘DG Connect’ is explicitly focussed on opposing centralising, locked-in trends. An example are the standards for EPUB3 (Publishing @W3C 2017), a major format within Europe for producing e-books, set against the Kindle format of Amazon in the US. In its design as a specifically interoperable and accessible format, EPUB allows for innovative practices. This was stressed again on the 2017 EPUB Summit in Brussels (EDRLab 2017). On the one hand, this shows technology invites experiments and hands-on work on new formats and electronic publishing workflows, but on the other hand the conflicting trends of locked-in formats and the build-up of industry monopolies, do make it hard to take the necessary innovative steps in publishing businesses.

It is our aim to see how we can exploit the trend towards openness and innovation. How to push the book towards reinvention? This inevitably leads to questions around what can be called, following Adema and Hall (2016), a ‘decentering’ of the book: ‘to reconsider all those ideas we have inherited with the book, such as those of the proprietorial author, the fixed and finished object, originality, copyright, and their accompanying practices of reading, writing, interpretation, analysis, and critique, and the extent to which we still need them’. To do so, it is needed to empower the skill set of professionals and researchers who are trying to develop and maintain an experimental, resilient, and innovative publishing practice; the smaller scale players who can put the centripetal forces to their own benefit and the book publishing industry at large.

It is our aim to see how we can exploit the trend towards openness and innovation. How to push the book towards reinvention? This inevitably leads to questions around what can be called, following Adema and Hall (2016), a ‘decentering’ of the book: ‘to reconsider all those ideas we have inherited with the book, such as those of the proprietorial author, the fixed and finished object, originality, copyright, and their accompanying practices of reading, writing, interpretation, analysis, and critique, and the extent to which we still need them’. To do so, it is needed to empower the skill set of professionals and researchers who are trying to develop and maintain an experimental, resilient, and innovative publishing practice; the smaller scale players who can put the centripetal forces to their own benefit and the book publishing industry at large.

The independent state of such players often means they are scattered and necessarily operating as small islands, unconnected to others and out of reach from partners who have the skills required to push innovation further. Academic research does not always find its way to the professional field and the innovative practices of the field often remain invisible to researchers. Bridges and links are essential to pass on knowledge and experience. We can use Robert Darnton’s ground-breaking essay (1982) on the circuit of book publishing to understand how this might be conceived. The field of trade publishing is, he shows, not made up only of books, but rather of players who operate in a circuit in which books are processed. Departing from a historical analysis he distinguishes, ‘Authors, Publishers, Printers, Shippers, Booksellers, Readers’ (Darnton 1982), to which we can add other roles in contemporary publishing, most importantly designers and, within digital publishing, developers. The functions are connected in a circuit, but the flow of the circuit is not always unproblematic. It is precisely such a flow within interdisciplinary teams that a hybrid publishing practice calls for, like the conclusive slogan of the DPT Collective summarises: ‘Editor, Designer, Developer, Unite!’ (DPT Collective, 2014)

People working in publishing can also be seen as having different roles which relate to what can be called ‘events’, as Darnton (2007) describes: ‘Adams and Baker distinguish five “events”: publication, manufacture, distribution, reception, and survival.’ The different practitioners working in the publishing field have to work together and rely on each other, in order to make the different events happen: publication, for instance, has to happen in concordance between author, publisher, distributor, and publicity staff, manufacture can only happen in collaboration between author, editor, designer, developer, and/or printer; survival depends on both publisher, developer, and broader institutions such as archives and libraries. In this research we will both consider the different roles within the communication circuit as pivotal, and maintain the perspective that roles are involved in different events of the publication process.

The need for a circuit with an unhindered flow of skills and products was also found in the research conducted by the research & development lab of the INC; the PublishingLab (PL) (Mapping the Field, 2016). It showed that in the landscape of innovative publishing practices as it exists nowadays, innovative publishers do not come in contact with innovative designers without a deliberate search; authors who start collaborative writing projects find it hard to find developers with the programming skills required to get the best result; while developers are in need of designers to make tools user friendly, et cetera. Darnton shows that emphasis on the participating roles in the publishing process can lay bare the functional barriers towards new and innovative practices, because books may be transferred along the ‘circuit’, but skills are not. This project is set up precisely as an exchange of such excellent skills, as is described within the goal of Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions.

The publishing industry and research is best understood from ‘praxeological perspective’ (Gilbert 2016), and especially in this innovation-driven project we benefit from the ‘practical turn’ in publishing research, which shows how experimental publishing research is finding its way into mainstream publishing. As Gilbert (2016) states, publishing can be viewed from the point of view of ‘maker culture’, and tactics employed in artistic practices ‘have been or are being explored in “mainstream” publishing too (…) As a consequence they have demonstrated an imposed willingness to experiment.’ To theorise this move, we now look at the role of technology in a post-digital publishing circuit, and use the ‘theory of publishing from the printing press to the digital network’ as laid out in Bhaskar (2013).

The post-digital as a practice in new forms of publishing can be seen in some of the most innovation-seeking small scale players in the European publishing field (both on the side of research, writing/editing, design, programming, and publishing/marketing) who consistently dedicate themselves to an experimental practice and some of whom we have sought out to collaborate with within the EXPUBLIQUA consortium. ‘Post-digital’ points to the state of digitisation that now has become the default in cultural practice and which affects cultural production from beginning to end. This has led to some interesting examples as documented in Ludovico (2012), Lorusso’s ‘Post-Digital Publishing Archive’ (without year), and Cramer (2014). The post-digital is a fruitful context for thinking about the role technology should get in innovative practices. For small scale publishers digital technology still remains disruptive to their business, even though technology has been a part of the publishing process for a long time and such technology is the primary means with which the book-making process occurs (in the form of word processors, desktop publishing programmes, et cetera.) (DPT Collective 2014). There is no turning back, but the affordances have yet to become clear and put to effective and relevant use within the cultural dimensions of what publishing entails.

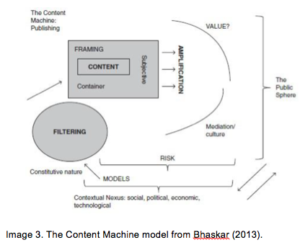

Bhaskar (2013) offers a useful theoretical framework to understand how contemporary publishing works. His theory revolves around four key points, which together constitute ‘the content machine’: framing, models, filtering, and amplification (see Image 3). Of these, the research proposed here is focused on the framing of high quality content using digital technology, while operating from a model of innovative and experimental practices, all the while acknowledging that ‘The precondition for publishing, one of those critical common factors, is content.’ (Bhaskar 2013)

Bhaskar (2013) offers a useful theoretical framework to understand how contemporary publishing works. His theory revolves around four key points, which together constitute ‘the content machine’: framing, models, filtering, and amplification (see Image 3). Of these, the research proposed here is focused on the framing of high quality content using digital technology, while operating from a model of innovative and experimental practices, all the while acknowledging that ‘The precondition for publishing, one of those critical common factors, is content.’ (Bhaskar 2013)

The frame, according to Bhaskar, is ‘that which content fills’. The concept of a frame allows for more flexibility than that of a ‘container’, the concept used widely in book research up till now; a container can for example be a paperback or hardback book, or an EPUB file, while a frame can account for more fluid publication processes, such as occur in the digital realm. The frame is not just an empty vessel to be filled with text, but has a direct impact on the way that content is conceived: ‘Frames are not just delivery systems or packages for content but content’s experiential mode.’ (Bhaskar 2013) Frame and content cannot be viewed as separate items; this is reflected in the intertwining of technology, design, writing, and editing practices that is put forward in this project.

The digital frame can take many forms. To operationalise it further, we define the frame of digital technology by its quantitative characteristics, investigating the means of automation in workflows, multi-language translation, image recovery and referencing, and algorithms used for data mining, personalised publications, and distribution, while focusing on maintaining a high quality in the contents thus created and used. This focus on quality is pivotal. As Daly (2012) states: ‘digital-only additions to texts should pass a two-fold test of utility. First, such additions should be immersive: they should appear to be natural extensions of the work, satisfying the curiousity of readers at the moment that these curiousities naturally arrive in the course of consuming the text. Enhancements must also be nontrivial. Loading up a reference work with links to Google Maps or Wikipedia offers little value the reader could not obtain independently.’ Publishing for a market of readers means to keep this criterion of ‘nontriviality’ in view at all times.

This leads to the ‘model’ that according to Bhaskar’s theory directs a publishing strategy. Models are equally individable from the content. Bhaskar stresses that models are not solely directed towards business: ‘political, aesthetic, religious and social as well as economic concerns shape models’. The model that directs the strategy in this project is innovation driven, taking into account what Pierre Bourdieu (1993) has termed symbolic capital. Publishers are ‘working in the field of “restricted production”, as opposed to the field of “large-scale production”’ (Bhaskar 2013). While making profit is a core concern of the publishing industries and their collaborators such as printers and booksellers, this concern is already weaker in the other roles of the publication circuit understood from Darnton (1982), such as authors, editors, and designers. Bhaskar concludes, following Throsby (2001): ‘Models are likely about making money and gaining cultural legitimacy at the same time.’ An innovation driven model combines both aims, seeking ways to ensure profit in an uncertain future and working towards cultural and societal development. With this we subscribe to what Ottina (2013) calls a ‘resilient’ publishing practice: ‘Resilient systems absorb disturbance, transforming when necessary to retain their essential function and identity. Resilience depends on the diversity that gives it a ready pool of responses to volatile conditions.’

Using the model of innovative experimentation should always come with a check on marketability. Digital innovation in publishing has some important steps to make in this direction. The evaluative notions of publication formats are still leaning favorably towards traditional print publications. Paper is seen as indicative of quality content, while e-books are mostly considered too expensive for the content they provide (Kircz & Van der Weel 2013). It can even be argued that the perceived value of the paper book has increased, by way of contrast to the e-book version. As Mulder (2016) states: ‘The e-reader … has thoroughly altered the status of the paper book, which has changed from a medium into an object.’ The low value attributed to e-books is in large part to blame on the focus, which has been on the development of the frame, while not regarding the link with the content and the reader.

An innovation driven model that is focused solely on the possibilities technology provides without taking the criterion of ‘nontriviality’ into account, only enhances the risk that Bhaskar recognises in publishing models: ‘because models are ultimately about value so they create risk as a by-product’. By acknowledging the underlying target audience of the professional field throughout the research process, the model of innovation used here will counter the risk Bhaskar notes. Even more, the countering of this risk is at the heart of this project, through knowledge exchange, training, the use and creation of open tools and a hybrid publishing approach.

Our focus on the frame as digital technology, and the model of innovation does not mean that we lose sight of Bhaskar’s other two points, being filtering and amplification. Having quality content is an insurmountable criterion of the participating publishers, which implies a heavy process of filtering. We strongly believe that for the experiments to be of value for a business, they have to be based on problems and issues arising from actual content. Working with actual high quality content will increase the incentive and will guarantee a result that can be used (marketed, sold, displayed, showcased) by the SMB’s themselves.

The above amounts to four basic points underlying the framework of the proposed future research:

1) hybrid publishing as fundament;

2) publishing for the reader (‘nontriviality’);

3) using technological qualities and affordances;

4) using high quality content.

References

Adema, J. and G. Hall 2016, ‘Posthumanities: The Dark Side of “The Dark Side of the Digital”’, in The Journal of Electronic Publishing 19:2.

Bhaskar, M. 2013, The Content Machine: Towards a Theory of Publishing from the Printing Press to the Digital Network, London/New York: Anthem Press.

Boek uit de Band conference 2012, https://networkcultures.org/outofink/past-events/boek-uit-de-band-2012/.

Bourdieu, P. 1993, The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on Art and Literature, Cambridge: Polity Press.

Cramer, F. 2014, ‘What is “Post-digital”?’, in APRJA, http://www.aprja.net/?p=1318.

Daly, L. 2012, ‘What Can We Do with “Books”’, in H. McGuire and B. O’Leary, Book: A Futurist’s Manifesto, Sebastopol: O’Reilly Media.

Darnton, R. 1982, ‘What is the history of books?’, in Daedalus 111(3): 65-83.

Darnton, R. 2007, ‘What is the history of books? revisited’, in Modern Intellectual History 4(3): 495-508.

Dieter, M. 2017, in ‘Zero Infinite #2 Postdigital Publishing’, Institute of Network Cultures, http://networkcultures.org/blog/publication/zero-infinite-2/.

Digital Publishing Toolkit, 2013-2014, http://networkcultures.org/digitalpublishing/.

DPT Collective 2014, From Print to Ebooks: a Hybrid Publishing Toolkit for the Arts, Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures.

EDRLab 2017, ‘EPUB Summit 2017 summary’, 15 March 2017, https://www.edrlab.org/2017/03/15/epub-summit-2017-summary/.

FEP 2017, The Book Sector in Europe: Facts and Figures 2017, Federation of European Publishers.

Gilbert, A. 2016, (ed.), Publishing as Artistic Practice, Berlin: Sternberg Press.

Kircz, J. and A. van der Weel (eds), The Unbound Book, Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2013.

Lorusso, S. without year, ‘Post-digital Publishing Archive’, http://p-dpa.net/.

Ludovico, A. 2012, Post-digital Print, The Mutation of Publishing since 1894, Eindhoven: Onomatopee.

Mapping the Field, 2016, PublishingLab, http://www.publishinglab.nl/mappingthefield/2016/01/19/mapping-the-field-visualization/.

Meyers, P. 2014, Breaking the Page: Transforming Books and the Reading Experience, self-published.

Mulder, A. 2016, ‘Mediatheorie van het e-book’, in Tijdschrift voor Mediageschiedenis – Vol 19, No 2 (2016), DOI: 10.18146/2213-7653.2016.266.

Off the Press conference 2014, http://networkcultures.org/digitalpublishing/events/22-23-may-2014/.

Ottina, D. 2013, ‘From Sustainable Publishing to Resilient Communications’, tripleC, 11 (2): 604-613.

Post-digital Scholar conference 2014, http://hybridpublishing.org/postdigital-scholar-conference/.

Publishing@W3C 2017, See https://www.w3.org/publishing/.

Rasch, M. 2016, ‘Discussion on possible future research in the field of (digital) publishing’, Out of ink blog, Institute of Network Cultures, https://networkcultures.org/outofink/2016/12/22/discussion-on-possible-future-research-in-the-field-of-digital-publishing/.

Rasch, M. 2017, ‘Digital Publishing Follow-up meeting #2’, Out of ink blog, Institute of Network Cultures, https://networkcultures.org/outofink/2017/02/10/digital-publishing-follow-up-meeting-2/.

Throsby, D. 2001, Economics and Culture, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Thurston, N. 2016, ‘The Mediatisation of Contemporary Writing’, in The White Review, September 2014.

Unbound Book conference 2011, https://networkcultures.org/outofink/past-events/unbound-book-2011/.