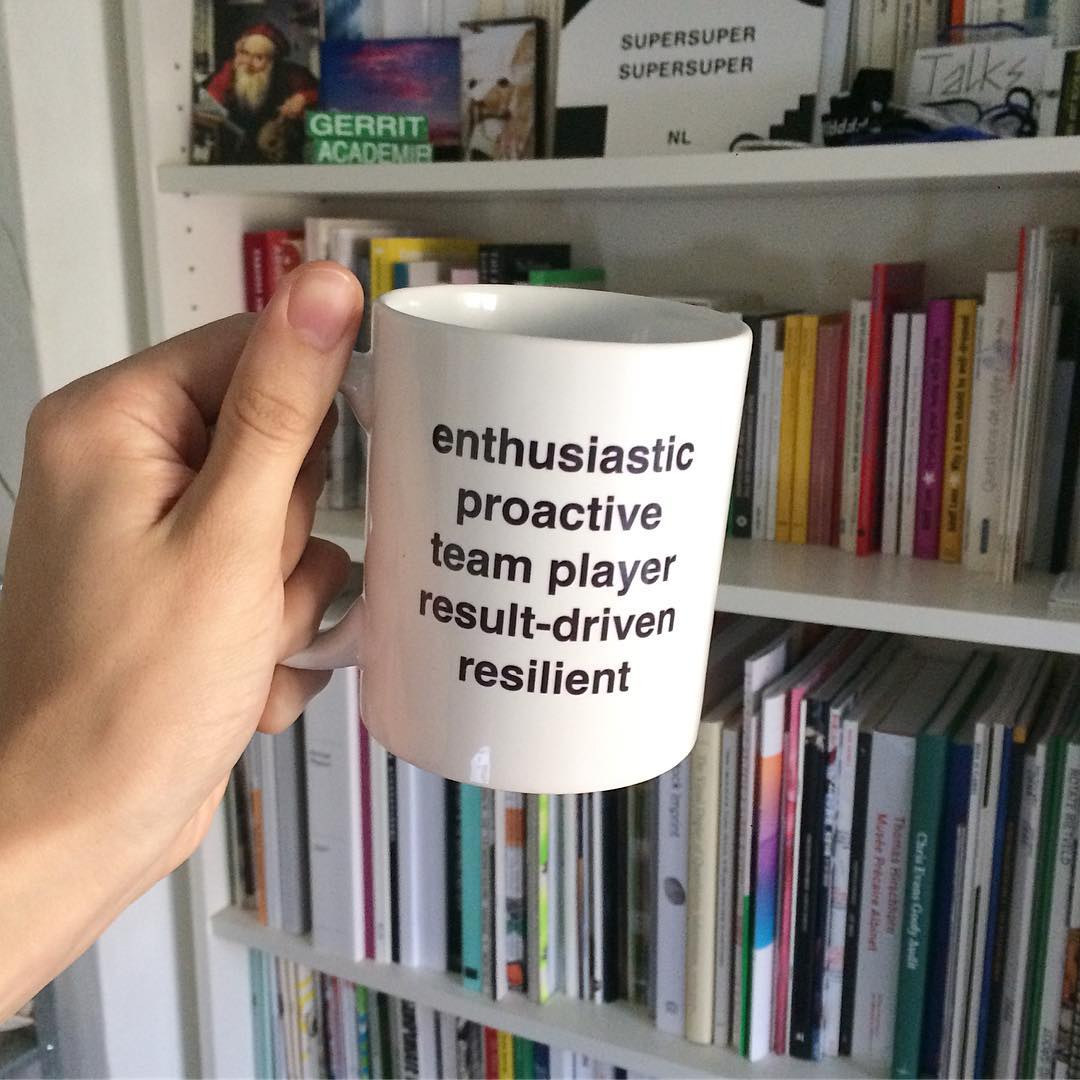

Revolution Mug ($30,00), Liat Berdugo and Emily Martinez.

Recently, I began to notice what could be called a trend, a series of coincidences, or simply the product of my carefully, yet unintentionally crafted filter bubble. I’m talking of a typology of merchandising (or merch-like products) created or tweaked to express precarious concerns in an antagonistic, ironic or illustrative way. In fact, I myself have produced some sort of precarious merchandising, in the form of ‘Shouldn’t you be working?’ stickers, à la StayFocusd.

F YOU PAY ME Shopper (£8,00), Intern Magazine.

Here’s a few examples. The F YOU PAY ME tote bag (£8.00) sold by Intern Magazine offers a motto that asserts the economic value of creative labor. For their Anxious to Make collaborative project, Liat Berdugo and Emily Martinez created a set of mugs that ironically reflects on the outsourcing logic of the sharing economy. Cory Arcangel’s Arcangel Surfware collection seems partly inspired by the positive thinking-imbued motivational macros that one can find on Instagram, and everywhere else.

‘Can’t Someone Else Do It?’ Mug ($10,00), Liat Berdugo and Emily Martinez.

Mugs, t-shirts, tote bags, flip-flops, pens, USB keys, caps, etc. There is no doubt that the emergence of easy-to-use online services like Zazzle, where these items can be printed on demand, fuelled the production of merchandising, or at least the creation of its virtual mockups. Is there anything particularly interesting about this? After all, there is nothing new about printing, say, a protest slogan or a funny quote on a t-shirt.

Fuck Negativity Slides ($59,95), Arcangel Surfware.

Some of the items are made by artists and exist as pieces, they are art as merchandising. But it seems to me that merchandising itself has its own autonomous aesthetic capacity. Think of the mug, an objet trouvé belonging to the increasingly alien space of the office. Possessing an aura of routine and work, the mug is the archetipical office prop. When I see a mug I immediately think of grey cubicles, Douglas Coupland’s Microserfs, the movie Office Space, and the somehow dreadful small talk with colleagues in front of the coffee machine.

Bill Lumbergh in Office Space.

I see the mug as a prop because it conjures a series of semifictional scenarios. Weirdly, these scenarios are able to evoke nostalgia. Why would one feel nostalgic of the miseries of office life? Maybe because it is a life that looks continuous, unchanging and therefore safe. The office mug belongs to a world in erosion. But I must say that the mug also fits another ambience, that of caffeinated work carried out from home, maybe while wearing a pijama. The coffee mug is there to keep me company when I stare at the screen and the breakfast seamlessly turns into lunch.

Volume magazine limited edition shopping bag.

Another way to explain the adoption of merchandising as an artistic medium could be based on the increasingly critical or at least skeptical stance of artists -and knowledge workers in general- towards concepts like personal branding and the related need to build a network. Consider the now classic shopper produced by Volume and designed by Daniel van der Velden and Maureen Mooren (if I’m correct). To me, the keyword is ‘victim’. Why should one feel a victim of success? Maybe because maintaining success and promoting one’s ("award-winning") worth to stay afloat is exhausting.

Unpaid intern t-shirt ($19,99), Luke Prowse, 2017.

Relating both to office culture and personal branding, the ‘unpaid intern’ t-shirt created is the perfect example of what I would call mugtivism, i.e. some sort of social or political critique expressed through merchandising. Created by graphic designer Luke Prowse, the t-shirt has its own body copy:

As minimalist in design as remuneration. Conceived to maintain high-visibility in even busy office environments our unisex unpaid internt-shirt is proven to enhance creative practise and increase business margins. Have the work experience of your life.

H&M purse. Photo by Nadine Roestenburg.

Then there are also items that are not merchahndising, but actual products that feel like merchandising, like the above H&M purse, seemingly a gadget produced by some sort of anxiety-related company.

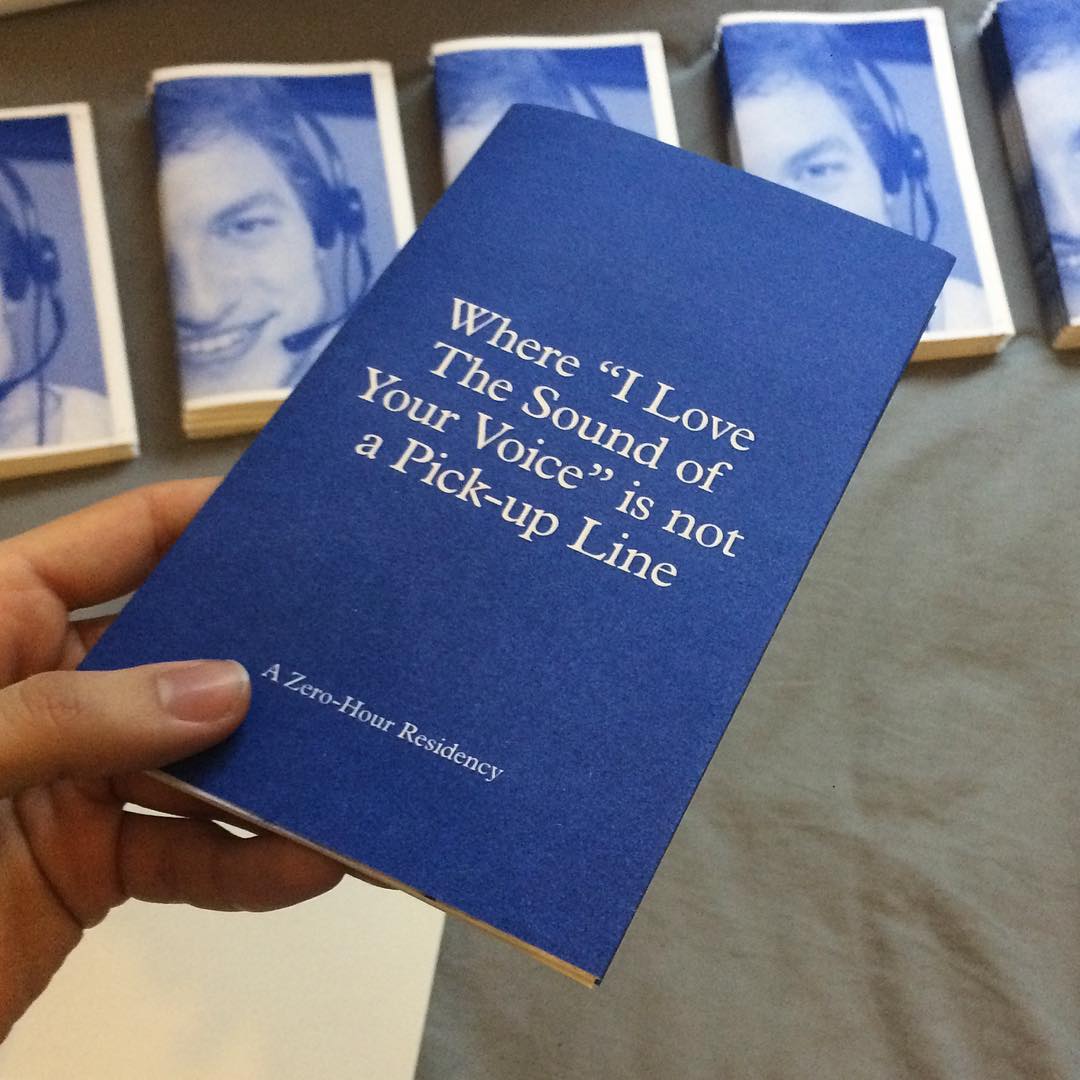

Where "I Love the Sound of Your Voice" is not a Pick-up Line, François Girard-Meunier, 2017.

Some days ago I had the chance to meet François Girard-Meunier and Alina Lupu. François is a Canadian artist and designer currently studying at Sandberg. His current practice revolves around various dimensions -emotional, existential, physical – of work. He recently published a little pamphlet aptly titled Where "I Love the Sound of Your Voice" is not a Pick-up Line. As you might have guessed, the booklet is about his experience as a part-time "international sales agent" in a call center.

Mug (not for sale), François Girard-Meunier, 2017.

Among the pages, there are some color images depicting a call center worker using or wearing standard and custom items like a headset, a pen or a cap. These items are not mentioned anywhere in the text, so one could guess that they are meant to function as a stealth, semi-passive protest or critique carried out while working. I find one of the items created by François particularly effective. It is a mug printed on two sides, where the one facing outwards (given that you’re right-handed) says "enthusiastic proactive team player result-driven resilient", while the one facing inwards says "anxious disengaged adversary satisfied vulnerable". What a better materialization of the cognitive dissonance, the dysphoria (as Raffaele Alberto Ventura calls it) characterizing the lives of entreprecarious subjects?

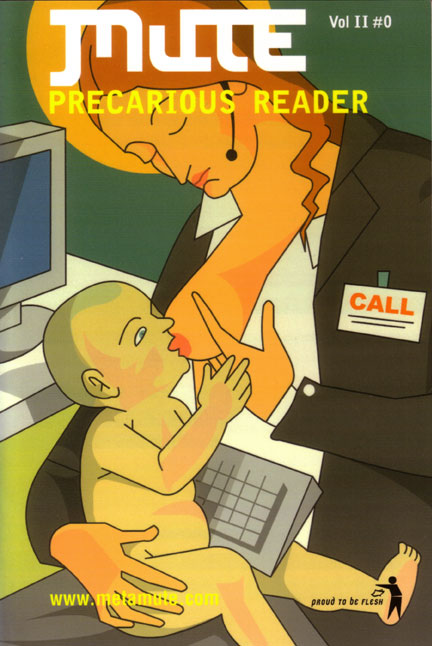

Precarious Reader, Mute, 2005.

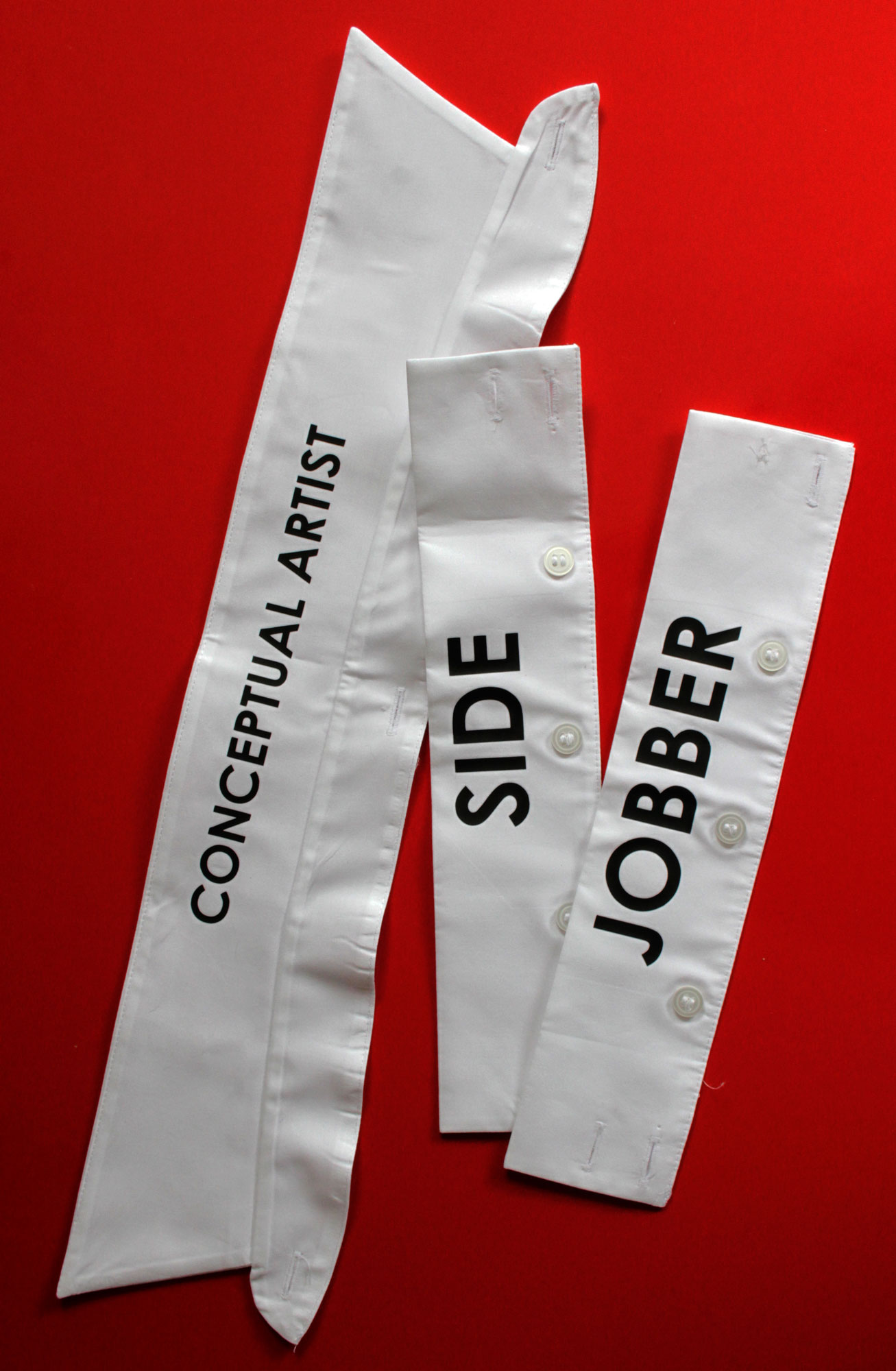

Alina Lupu is a Romanian artist exploring the precarious conditions of life in the arts. In her recent performances, the multiple identities of the young graduate (like that of the emerging artist and the intermittent worker) become intertwined; roles that are generally -and somehow deliberately- understood as distinct come together and clash. While François offers an update to the narrative of the call center agent, which was the stereotypical icon of the precarious worker in the mid-2000s, Alina couples the fragile aspirations and self-attributed labels of creative workers with the mundane activity carried out within the expanding gig economy. Conceptual artist VS side jobber, money VS prestige, autonomy VS subjugation, material VS immaterial labor are only some of the dichotomies that she addresses.

From Alina Lupu’s online portfolio.

Alina, who works for (or should we say ‘with’?) Deliveroo, has appropriated the bike delivery aesthetics (phone, jacket, cubic backpack) to place the banality of the ‘side job’ at the center of the museum, the gallery, and the conference panel, each of them being an environment that at various levels relies upon this eclipsed type of work. In The Living Museum, she walks through the Stedelijk wearing delivery equipment deprived of any recognizable brand. The white cubic bag resonates with the space where she roams; another white cube, just bigger. Some people notice her, some other don’t. What is she delivering? Does it actually matter? For the courier, it surely doesn’t. Her phone is guiding her. Is she lost? Maybe she’s looking for the museum itself, which indirectly feeds on Alina’s labor. Delivery delivers people.

The Living Museum (Minimum Wage Dress Code), Alina Lupu, 2017.

Here in the Netherlands, Deliveroo and Foodora bikers are everywhere. Their equipment is a strong visual signifier of the change that is taking place around labour. Right now, it feels like an invasion, but soon it will turn into the norm and, as such, it will become invisible. We will grow so much used to the cubic backpacks that we won’t be able to see them anymore. When Alina, a bit like in They Live, removes the superficial layer of this equipment made of brand colors and logos, she reveals the barebone operational and corporeal dimension of this type of work. Through a process of abstraction she presents work in its concrete, material form: a person wearing a backpack guided by a phone.

Playtime (Minimum Wage Dress Code), Alina Lupu, 2017.

I bet that in the coming years plenty of artworks and performances inspired by the courier aesthetic will pop up. Is that a bad thing? Not really. Aloisi, De Stefano and Silberman recently pointed out that gig workers offer us a "prophecy" of the near future of work. More people interested in this evolving reality means more people willing to understand it and hopefully to play a role in it.

Also published on Medium.