Image by Sebastiaan ter Burg

Michel Bauwens and The Promise Of The Blockchain

Thursday 25 February 2016

This event was organised by FIBER and De Brakke Grond and was part of FIBER’s Coded Matter(s) series and the year programme of the De Brakke Grond ‘All Future Memories’ De Brakke Grond, Amsterdam

‘Michel Bauwens and The Promise Of The Blockchain’ was attended by both artists and entrepreneurs eager to be at the cutting edge of the latest speculative boom in disruptive technology – the Blockchain. The evening program consisted of four presentations that demonstrated the promising potential of Blockchain technology in different areas of society.

It began with a basic overview from Michelle Kasprzak who acted as moderator, explaining in layman’s terms the fundamental principles of Blockchain and providing clear examples of it’s use in social contexts. One of those examples is Mazacoin a crypto-currency that is used to trade between different native American tribes in Dakota, USA. The crypto-currency aims to create a sovereign state for the indigenous people, helping to protect them from global market forces by facilitating their own trade and local economy. Localized movements, informal economies and community currencies were also part of the picture painted by Micheal Bauwens who delivered the opening keynote. Bauwens described the social context for the rise of the commons and explained how Blockchain and crypto-currencies can assist in this change of what he called ‘global value regimes’. Bauwens anticipates a dramatic change in dominant value systems and supports this claim with the view that dominant value regimes change roughly every 500 years. He shows a linearity of trade from early civilization to the fall of the Roman Empire, and from the industrial revolution to the extractive economy we have today.

Image by Sasha Katz (2016)

Bauwens wants to show how the economy is moving from an extractive model to a generative model – one of value production – and insists that there is a real bottom up transition movement towards new systems of value that are not based on market costs but on social benefit. P-2-P values and initiatives towards a new commons have gained a lot of traction in different communities around the world and can be followed on the website http://commonstransition.org/. Bauwens uses the term ‘net-archical’ to describe the extractive mechanisms of major online platforms such as Facebook & Twitter and articulates the extractive & plundering nature of share economy services such as Uber and Airb’n’b. Bauwens makes clear distinctions between what he calls ‘Net-archical capitalism’ (Facebook, Uber) that are centralized companies interested in profit and ‘Global Commons’ initiatives such as Wikipedia & Couchsurfing, which are not for profit and geared towards collective social benefit.

Bitcoin as a currency has turned into a de-centralized, distributed form of free market capitalism that should not be viewed as a new form of value exchange, but as another currency that is traded on the stock market.

After clarifying the blurred lines between share economy principles and digital monopolies Bauwens goes on to address some common misconceptions about the crypto-currency Bitcoin. Bauwens highlights how Bitcoin, in attempting to be completely de-regulated from the central banks, has become completely dependent on free-market capitalism. For him, Bitcoin as a currency has turned into a de-centralized, distributed form of free market capitalism that should not be viewed as a new form of value exchange, but as another currency that is traded on the stock market. It is Bauwens’ reservations about Bitcoin that frame his vision for a post-capitalist society and new value regime(s) that can be created by Blockchain, not Bitcoin. In light of this, Bauwens is confident that Blockchain technology (the technology that powers Bitcoin) can transform how value is produced and exchanged in the way we exchange physical and material goods similar to how networked technologies enabled the knowledge commons in the rise of the information age. For Bauwens, the application of Blockchain is an opportunity for de-centralized peer produced initiatives to take hold in the physical material world through logistics, transport and smart technology. Initiatives such as sustainable energy that can be collectively managed and distributed via a Blockchain ledger, or car-pooling where the profits are automatically distributed within social groups. He argues that we can create a new value system by taking the generative, open, p2p models of the Internet and integrating them into physical and material goods with Blockchain applications.

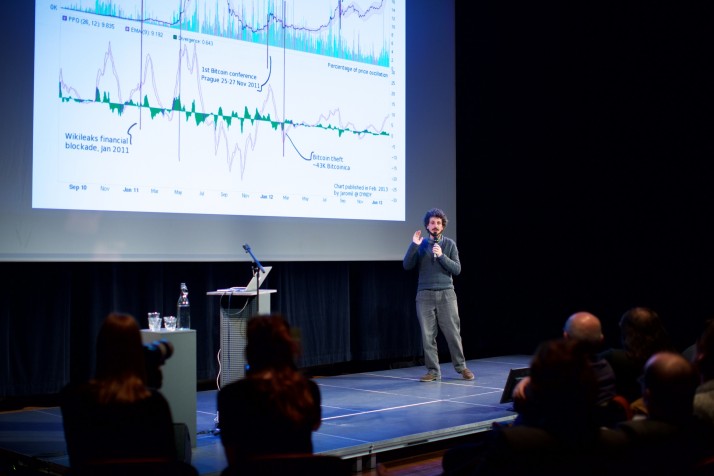

The next speaker was Jaromil from D-cent – a EU funded organization that has been exploring and developing tools for new forms of democratic social governance.

The next speaker was Jaromil from D-cent – a EU funded organization that has been exploring and developing tools for new forms of democratic social governance.

D-cent produces digital programs, code and software that aim to change societal structures to more open, democratic forms of organization. Perhaps this is why Jaromil was not immediately interested in Bitcoin until it was used to defend and support Wikileaks against the financial blockade inflicted by Visa, Mastercard & Paypal in response to the leak of US diplomat cables in September 2011. This collective action and mobilized resistance sparked Jaromil’s interest in Bitcoin as a de-centralized tool for collective social organization. However, as Jaromil points out, the software behind Bitcoin is what you call a ‘trustless system’: it assumes every single user is corrupt and fraudulent in order to protect and secure itself from being hacked. This model, he argues, suits one type of transaction but there are plenty of other reciprocal forms of exchange that occur within informal economies that could become recorded transactions. For example, what about lending someone you know some money, with no agreed set time or date to pay it back? This type of unconditional gifting is difficult to program into digital lending systems.

The after-effects of social media platforms have perpetuated an insatiable desire to measure and quantify every social relationship into a numerical value.

This is why Jaromil helped produce FreeCoin, an e-wallet created for exchange and trading between friends; he calls it a ‘social wallet’. FreeCoin is a social currency that adapts the ‘proof of work’ concept used in Bitcoin to validate social gifting and exchange within communities. In experimenting with the proof of work concept Jaromil is re-defining how value is expressed and exchanged by people and how technology can measure and distribute that value. By putting people at the center of the design of FreeCoin, Jaromil wants to re-instate trust into a trustless system.

Image by Sebastiaan ter Burg

Although it is an admirable concept I am concerned there is a disheartening ramification in turning the quality of a person’s social relations into a cypto-currency. In order to account for the value shared between friends and social groups, FreeCoin software would need to measure and quantify those friendships to validate it as ‘social currency’. I can understand the need to design an electronic currency that reflects and incorporates relationships and trust between social networks, however using social relations as units of economic value descends from the commoditization of friendships used within social media businesses. Social media platforms such as Facebook use friendships and social groups to create targeted advertising campaigns that turn every encounter, every click and every like, into quantifiable economic figures. The business social media platform LinkedIn explicitly quantifies friends and relationships with ratings and scores to aid the unemployed find work in the labor market. The after-effects of these platforms have perpetuated an insatiable desire to measure and quantify every social relationship into a numerical value. Although FreeCoin is not directly calculating market value based on your social relationships, it is adapting a numerical scoring model for validating social relations to produce a unique ‘social’ cypto-currency. The prospect of scoring friends with a numerical value between 1 and 10 and using this number to facilitate and record informal exchanges seems anything but social. I hope I am not alone in feeling that a meritocratic scoring model for validating social relations with tokens would be an implementation of the worst aspects of social media business models and I fail to see how digitizing the emotional value between friends into a quantified currency could be empowering for communities.

As an associate at Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard Law School Primavera De Filippi is concerned with how Blockchain can transform law and create new forms of social governance. Although Filippi acknowledges that smart contracts cannot and should not replace all legal governance, she does believe there are many outdated legal procedures that could be converted into smart contracts. When you combine smart contracts and networked technology such as the Internet of Things you are able to enforce contracts without human mediation.

The libertarian attitude towards distributed de-centralized governance contradicts and demolishes core socialist values.

For example, I might one day buy a car but then be unable to keep up with my credit repayments; with a smart contract the car could be automatically locked down until I could fulfill my payment responsibilities. A crucial issue regarding this is that law is intentionally ambiguous, this allows for a certain degree of human agency for individuals to create their own moral and ethical choices within a legal framework. That is why lawyers often describe legal procedures with the cliché ‘every case is unique’. This is why the prospect of autonomous automated legal governance is something to be concerned about and not something that should be easily gift wrapped into the de-centralized libertarian package; that is the idea that ‘distributed technology will be empowering for everyone’. As David Golumbia outlined at Moneylab#2 in December last year (video), the libertarian attitude towards distributed de-centralized governance contradicts and demolishes core socialist values – such as state regulation and institutions such as the welfare state. The potential for automated agents to enforce law and social governance should be examined with great caution, because in distributing power this way you simultaneously reduce autonomy of individual citizens and the power of the state. Distributing the power for anyone to create their own law enforcing applications (with software such as Ethereum) is socially democratic in production (everybody gets to make their own digital contract) but could lead to a regime of networked governmentality in reality. Although this sounds like a libertarian dream for a few it could be a de-centralized panopticon for the many.

Image by Sebastiaan ter Burg

The final speaker to take to the stage was Vinay Gupta who gave an energetic presentation on the history of databases and the cultural and social origins of Blockchain. Gupta historizes the evolution of the database from the perspective of an I.T. engineer, summarizing the complexities of older systems and the beautiful simplicity of a single universal networked database – the Blockchain. He exclaims that the Blockchain ‘fuses together network and data in a away that was never possible’. Gupta continues to identify the social and cultural origins of Blockchain as a consequence of cryptography and cypherpunk hacker culture. The cypherpunks were digital activists who used cryptography and other (open source) computer programming tools to ensure privacy in electronic communication to hack and oppose state governance. Gupta, as a self-confessed cypherpunk, sees Bitcoin and Blockchain as a linear outcome of the anti-authoritarian digital movements of the 90s and like many Bitcoin-enthusiasts, he is radically anti-authoritarian and takes any opportunity to criticize current state or democratic organizations as centralized hives of power and control. Gupta dramatically over-simplifies this dichotomy by calling it “The Lawyers vs the Technicians”, a social struggle between working classes (computer programmers) and the privileged elite (technocrats). By contextualizing the Bitcoin phenomenon within the cypherpunk movement and presenting the history of databases the audience at Fiber may have been left still wondering about the social relevance of Blockchain, but are at least assured of its technical significance.

Image by DeepForger (2016)

All the speakers presented their individual versions of bright promising futures that use Blockchain technology. It is very appealing to believe in all the promises Blockchain technology poses to solve because of the libertarian political rhetoric that surrounds it. We are repeatedly led to believe that it will create a more democratic and equal society however I am not convinced that any of the uses of Blockchain presented at this event will fulfill that promise. The anticipation surrounding Blockchain is magnified by anti-authoritarian rhetoric and juvenile ‘taking back the power’ attitude with de-centralized software and open source applications.

Examples of Blockchain technology liberating communities to collectively manage their resources in a de-centralized or autonomous manner are still abstract thought experiments or draft prototypes at best.

This promise relies on citizens using the available software to liberate themselves from the current tyranny of power by designing ‘world-changing’ applications. The examples of Blockchain technology liberating communities to collectively manage their resources in a de-centralized or autonomous manner are still abstract thought experiments and draft prototypes at best. Without any large-scale examples of Blockchain applications successfully supporting communities and the commons, the remaining attraction is the renegade; anti-authoritarian attitude that distributed p-2-p technologies will somehow overthrow governments and central banks. What is scarcely mentioned within the Blockchain bubble is the banks appropriation of Blockchain as the newest electronic payment system. The major banks and financial companies were quick to start investigating and incorporating Blockchain early on and formed the R3 consortium in 2014. The R3 consortium is an unorthodox collaborative organization consisting of 43 of the world’s largest banks to work together to investigate how Blockchain technology could improve the world of finance. Just last week the Bank of England announced its very own bitoin crypt-currency replica called RSCoin, built on a private and centralized Blockchain. This is another massive blow for Bitcoin advocates as it appears that the technology will become the basis for global finance and the de-centralized, open source, p-2-p public ledger will be replicated into a private, centralized and controlled system to serve the banks.

The desire to uproot the dichotomies of power with a distributed public ledger should be met with greater consideration and questioning of what would actually benefit from becoming

de-centralized, distributed and autonomous.

Consequently, the political rhetoric surrounding Blockchain as a tool for anti-authoritarian, de-centralized freedom is shadowed by its imminent widespread dominance in the financial sector. Unless you are working in the financial sector, there is currently very little impetus for individuals to begin implementing Blockchain into their day-to-day lives. The desire to uproot the dichotomies of power with a distributed public ledger should be met with greater consideration and questioning of what would actually benefit from becoming de-centralized, distributed and autonomous. At the end of his presentation Gupta emphasized the emergence of Blockchain as a class war by commenting “until now it has been historically impossible to re-write the political system from the bottom up”. If you want to frame the expansion of Blockchain as a political revolution than I would go one step further to ask what are you fighting for? Social justice and inequality won’t be solved by any technical application so if your building applications from the frequently termed ‘bottom-up’, take greater consideration to ask who it is for and who would it benefit? This way the democratic social values that Blockchain technology consistently promotes might begin to permeate to the rest of society rather than remain entrenched in a power struggle between what Gupta describes as “The battle between the lawyers vs. the technicians”.