Fiverr, the online marketplace that connects freelancers to the "lean entrepreneur", recently launched a new campaign under the hashtag #InDoersWeTrust. The accompanying commercial features the lives of some of these doers. They make Skype calls with the other side of the world ("Ni Hao Ma") from a restroom, they unremittingly pitch their business to family, friends and strangers, they "get shit done" and are constantly available, even while they’re having sex. The portrayed doers are white and mostly female, even though the one ending up on the cover of Entrepreneur magazine is a young man.

This campaign signals a new phenomenon, a shift in the entrepreneurial role model: what we see here are not the typical entrepreneurs celebrated by the media, with their future oracles and game-changing technologies. The new entrepreneur is neither a visionary, a Harvard dropout, a guru, nor a tech genius. The new entrepreneur, the doer, is just busy.

The fast-paced rhythm of the commercial reminds me of blockbuster movies from recent years like Birdman or Whiplash, both exploring the dilemma of personal success and self-determination. The non-stop 24/7 vibe of the Fiverr ad, the subliminal anxiety that drives it, with its pragmatic, energy drink-fuelled relentlessness (can you hear the heartbeat?) looks like a managerial détournement of Trainspotting‘s Choose Life generational manifesto. Here, however, choosing life means neglecting the needs of one’s own body. Ultimately, it means ignoring death, which makes its appearance in a short cameo. Isn’t this ad somehow similar to 2014 Cadillac’s celebration of the American hard working ethos? Yes, but with a difference: all the luxury is now gone.

The new entrepreneur doesn’t care about ideas ("my little sister has ideas…"). The doer is certainly not a dreamer –because who has time for sleep anyway? As a friend of mine puts it, the archetypal Fiverr entrepreneur is the dark horse, "the underdog". Yet, underdogs can make it, and when they do, they can dedicate a couple of hours to some random humanitarian activity, "save the rhino" or whatever.

Doers despise the high-tech industry. No more Zuckerbergs or Musks please. It’s time to "beat the gurus, beat the trust funds kids, beat the tech bros". No room for unicorns here, fairytales are for kids. The drones who work in finance –bankers, VCs– are (literally) sharks to the new entrepreneur’s eyes. Not to speak of the geek gangs… how silly they look with their ridicolous gadgets. Forget brainstorms, general meetings and all the other time-sucking post-bureaucratic company rituals. What Fiverr is promoting is an entrepreneurial populism, where ‘we, the doers’ are going to smash the techno-financial elite.

Before doers, there were makers. But they’re now a thing of the past. Who can afford the beautiful accidents of 3D printing or the unexpected blips of an Arduino-powered speaker? In these times of creative austerity, what we are left with is the dry sternness of a todo list. "Above all –and this is important– do, because thinking big stays just thinking". Actually, listen to me, don’t think at all. It’s just a waste of time.

The Fiverr campaign seems to draw inspiration more from the mantras of management schools (‘the hustle’) than from the cheerful do-gooderism of tech startups (‘make the world a better place’). Of course, ‘community’, as well as ‘quality’, is still considered a prominent value. How could it be otherwise when the collaboration with graphic designers from Bangladesh or web developers from Poland is the norm?

But who actually are the doers? Are they the ones who offer a service on Fiverr or those who purchase it? While the campaign is targeted at buyers more than sellers, the difference between them is tiny. Both are users of the platform, both will probably need some kind of product or service offered by other sellers, be that a logo or a a translation. Every buyer is someone else’s seller, a seller giving 20% of their share to the platform. Welcome to the gig prosumerism, where what Josh MacPhee described for Kickstarter users become true for many more independent professionals:

Our goal—our imperative—is to harden ourselves and our projects into cohesive, likable, and salable commodities. We wake up as brands, joyously exulting in these flattened, logo-like versions of ourselves. Clean and efficient with soft, smooth corners and antiseptic Helvetica expressions. What is not to love about these new forms, so sleek and attractive on the outside, with the promise of aiding us in the fulfillment of the last remaining human right in our society: the right to be an entrepreneur?

Fiverr might soon become as natural as Facebook when it comes to organizing the work relationships of isolated workers. Maybe freelance labor will be automatically, thoughtlessly called ‘Fiverr work’. What shall I include in my business card? A link to your Fiverr profile is more than enough! But then, we know how it goes, the platform will change its terms of service. This will make users unhappy. Some of them will try to find or build other ways, they will lament the bygone past. But it will be too late. "Don’t you have a Fiverr account? No? Are you an actual professional?" In turn, ‘entrepreneur’ might become a derogatory term, one used to indicate the pariahs that offer their services outside of the platform. This is why entrepreneurs will set up a commune in the desert where the economy will be based on barter instead of money… Ok, enough of science fiction and back to the campaign.

Photo: @b_cavello

What really caught people’s attention wasn’t so much the commercial, but the posters disseminated by Fiverr. One in particular caused some stir on Twitter. In this poster we see a black and white close-up of Christina, a doer who "has nothing to lose", accompanied by a text in bold, capital letters:

You eat coffee for lunch. You follow through on your follow through. Sleep deprivation is your drug of choice. You might be a doer.

The main reason why people got upset is that the poster glamorizes an unhealthy work routine. It’s hard to believe that this reaction wasn’t somehow anticipated by the creators of the campaign. After all, they’re workers too. Perhaps, while brainstorming, they had an illumination: they realized that there is no such thing as viral as our perverse relationship with work. This poster is a like a distorting mirror, what makes it effective is that we do relate. We get angry at Fiverr because we don’t feel totally comfortable with our so-called work-life balance.

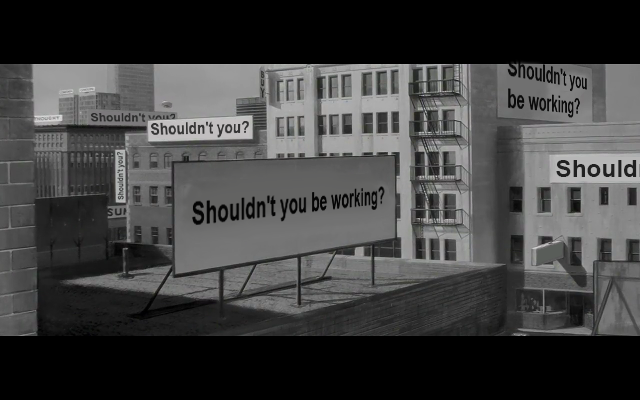

Some time ago, inspired by Guy Debord’s "Ne travaillez jamais" graffiti, I started producing a series of “Shouldn’t you be working?” stickers. The slogan comes from StayFocusd, a browser plugin with more than 600,000 users. When your allotted time on social media and other procrastination sites is over, StayFocused show you this text. My selling point was the following:

Why keeping lazy-shaming only on screen? With the Shouldn’t you be working? sticker, work anxiety will always stick around.

As I hoped, people put the stickers in the most disparate spots –fridges, windows, ovens, toilets, trains– thus ironically confirming that the voice pronouncing this obsessive refrain is primarily in our heads, that we are our own regulating device. My goal with the sticker was to materialize the work ethic dystopia we live in, to externalize it somehow in order to reject it.

Photo: Nadine Roestenburg

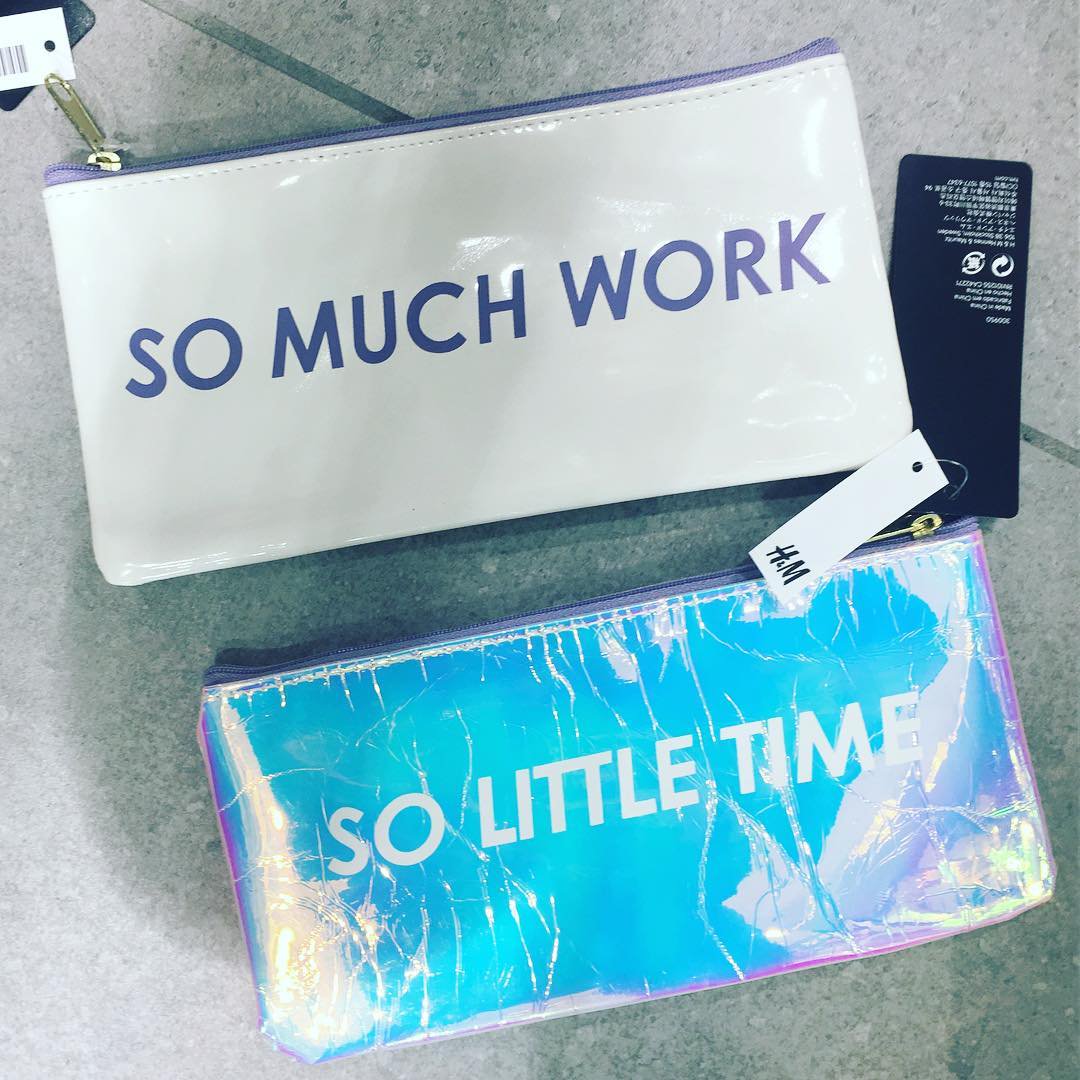

Then, I received a picture of a glossy H&M purse, made in China, with a print, in pseudo-Supreme style, saying "So Much Work, So Little Time". At that moment I could finally instinctively grasp what Mark Fisher meant by boring dystopia, a dystopia that doesn’t provoke any consternation, that has become the new normal. A dystopia that is unrecognizable because it’s like water for the fish. When Fisher coined the concept, he had in mind the dire state of "neoliberal England" where citizens don’t have the means to care anymore:

It’s not that they don’t care, but in a city like London, or any intensely pressured urban metropolis—add to that the pressures of capitalist cyberspace and people just feel like they perpetually have no time."

What the H&M purse and the Fiverr campaign show us is that boring dystopia has gone full circle, that it can exhibits itself unapologetically, that it is immune to irony, that –my friend Dave got it right– we "can’t tell the difference between tactical media and actual media."

We are used to think of hard work as an expression of integrity, but both hard work and integrity are now insufficient. Not just hard work, but nonstop work is becoming a status symbol: according to a forthcoming paper for the Journal of Consumer Research, the lack of leisure time is commonly understood, at least in the US, as a signifier of prestige and power. Is this the reason why US citizens, especially self-employed, work more than 40 hours per week? Or is the "no-life" lifestyle a necessity to keep the wolf from the door? One possibility doesn’t exclude the other. As Kate Aronoff puts it,

One of the labor movement’s hallmark victories—an eight-hour workday—is now being eroded on each end of the economic spectrum: by start-up wunderkinder toiling late into the night as well as by low-wage service workers juggling multiple jobs just to make rent, one of which might happen to be as an Uber driver.

Maybe nonstop work is seen as a status symbol because work itself is increasingly becoming a scarce resource, a luxury. But when success is indicated not by the benefits of excessive work, but by excessive work itself, there is something broken. This is why a stigmatization of extreme busyness is urgently needed.

But, as we saw with the Fiverr campaign, radical busyness can’t be effectively addressed by merely showing, ironically or not, how preposterous it is. Instead, the wave of indignation provoked by the poster should be turned into a straightforward demand, a radical claim able to break the veil of work ethic dystopia and open up a new horizon of possibility.

A 3-Days Workweek

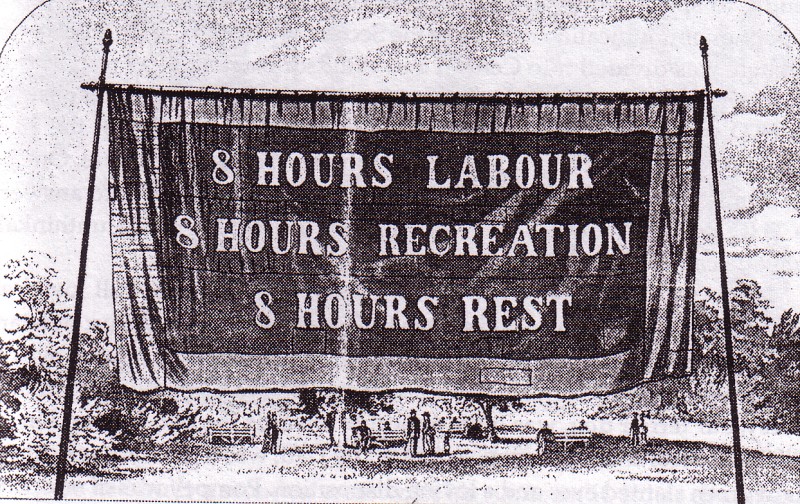

In most Western countries the 8-hours workday is taken for granted. This wasn’t the case at the beginning of the 19th century when a worker could spend between 10 and 16 hours in a factory on a daily basis. Crucial to the decrease of such standard was the short-time movement, coalesced under the slogan "eight hours labour, eight hours recreation, eight hours rest". The motto, probably inspired by the writing of Welsh utopian socialist Robert Owen, spread globally –in Melbourne there is even a monument dedicated to it. Isn’t it a beautiful catchphrase? So elegant and concise (888 in short) that it reads almost as a mathematical formula or a line of code.

Melbourne, 1856

Like the notion of the weekend, the division of the day in three equal parts is now so ingrained in our minds that we consider it natural. But as we know, it is somehow too rigid and impersonal to properly describe contemporary labor. For many of my friends, the idea of punching the clock is dreadful while at the same time the possibility of working on a Sunday doesn’t sound crazy at all. This is why a more malleable imagination of work is needed, one grounded in our current social reality, one that would leave room for experimentation.

A 3-days workweek, this is my humble proposal. Dedicating three days to work, possibly in a flexible way, means that the biggest part of the week can be devoted to vocational activities, be they self-care, education, volunteering, rest, etc. Is more work your vocation? That’s fine, but at least don’t humblebrag about it. Shall we prevent people from wasting their four-days weekend on their couch watching TV? No. A genuinely free time should be free of paternalism. The 3DW is a means to construct a scenario in which life is not inevitably exhausted by work. It can be interpreted as a concrete goal, but also as a discoursive hypotesis. The 3DW is a cultural more than a legislative demand. In some countries, for some people, it is already a reality.

What allows a flexible 3-days workweek? Stability in the first place. One of the keywords of the late 2000s movements against precarization was flexicurity. If I’m a freelancer and I don’t know whether i’ll be able to get other jobs in the near future, I will fill my schedule as much as I can. My time management will be driven by fear, haunted by the spectres of failure and poverty. The same logic often applies to studios and companies: they take as many jobs as they can while they can, since nobody knows about tomorrow. Thus, whether freelancers or employees, many people work late. And if they don’t, they aren’t farsighted enough.

Financial and professional instability is now the default. It appears as a permanent condition. Given this state of affairs, economic foresight shouldn’t be delegated to single workers, it shouldn’t be a personal responsibility. Governments must prevent a gloomy future from blackmailing its citizens.

Do we really want to eat coffee for lunch? Do we actually feel comfortable when we brag about sleep deprivation? Are we willing to identify as doers or are we culturally and materially forced to? A movement around a 3-days workweek, with its corollary demand for stability, might help answer these questions. Who’s in? Where do we start?

Also published on Medium.