Inge Ejbye Sørensen has worked for more than a decade as an award winning documentary-maker for the major 4 TV broadcasters in the UK (BBC, Channel 4, Five and STV). This creative industry is also her research area as an academic. She is currently at the Centre for Cultural Policy Research (University of Glasgow, UK), where she analyzes the micro dynamics of the individual documentary-makers (content, aesthetics, experience with the digitization shift and its implications) as well as macro dynamics of the whole industry (production process, distribution networks, alternative finance schemes like crowdfunding, and cultural changes).

Her article Crowdsourcing and outsourcing: the impact of online funding and distribution on the documentary film industry in the UK is a clear, thorough and insightful discourse at many levels. The trend of migrating from UK’s traditional funding model of the broadcaster as commissioner, funder and distributor to that of the filmmakers’ own crowdfunding, crowd investment and online distribution networks is not just a shift in revenue model, argues Sørensen – it’s most importantly, albeit less visible, about the cultural and creative shifts.

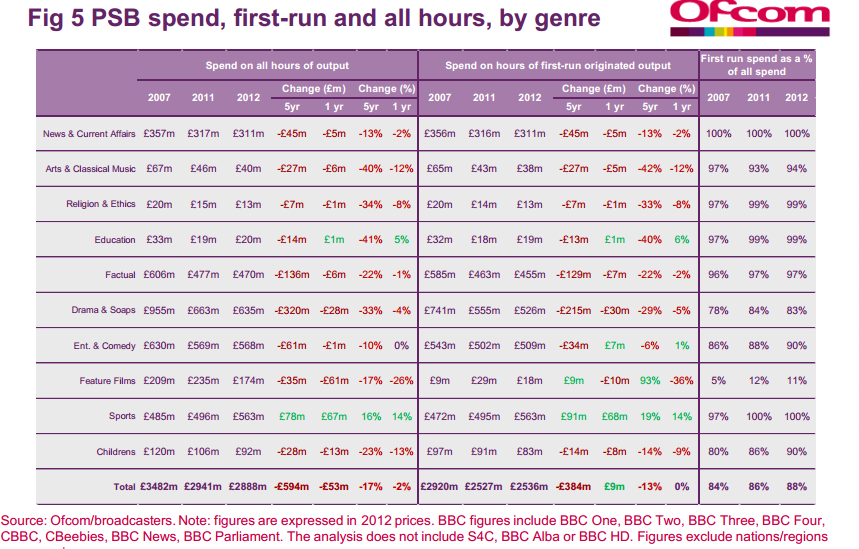

Broadcasters, details Sørensen, have been and are major decision makers in the documentary industry in the UK. Unlike in many European countries, where a single documentary can receive money from a wide range of public and private sources, in UK’s particular model it is a broadcaster that (fully) funds it. Nevertheless, points out the author, these broadcasting entities are public, and therefore commercially-sponsored (an interesting and ironic model itself). With the private sponsor’s advertising budgets moving to online audiences, there have been yearly cuts in funding for factual programming and documentaries on TV.

While another justification for this could also be the reduced production costs of documentaries (which now have much lighter and technologically-capable equipment, which also ” allows one person to the job of many”), in reality the airing of a documentary brings less return of investment than other type of programmes (like drama or entertainment). Its characteristic as a one-time screening event doesn’t fit the advertising model of returning visitors, which drama episodes fulfill, nor does its ethics allow products placements. Therefore, argues Sørensen, this has effective implications in what type of productions are being supported: long term (series and episodes), big budgets (that can be satisfied by a handful of strong sponsors), suitable topics (“the broadcaster’s commissioning editor will typically also act as an executive producer and potentially have a significant say in the editorial of the film”)(Sørensen, 737), often involving celebrities and a first-person narrative style.

In this context, it is the no-to-low budget documentaries particularly that migrate to crowdsourcing, crowd investment and P2P online distribution as alternatives. While these come with financial rewards, opportunity of engaging audiences and editorial independence, the role of the artist slides to new, unforeseen responsibilities (“documentary-maker, PR person, sales-woman, fundraiser, public speaker and distributor”)(Sørensen, 738). While it’s an open space for all creatives, reality shows that particular productions like long-term and/or high cost productions (preferred by broadcasters) are not really fit for succeeding on the alternative model. Hence, coins the author, the resulting polarization of both budgets and type of productions that is being made by the two models of financing.

Furthermore, Sørensen argues ,there are some factors that can determine success in online funding. Interestingly, these refer mostly to the prestige of the filmmakers, their strong networks (that can financially contribute) and an appealing topic. Notions like trust, credibility, impartiality and high quality are just as vital in these alternative funding schemes. Whereas normally it is big broadcasters and cinema festivals that are deeply embedded in the mindset of the audience as vowers of artistic value and safeguards of quality knowledge (and thus, offering the documentaries the much needed social capital to appeal to the audience), it is relevant to analyze where the new authority and social capital resides on crowdfunding platforms and P2P online distribution channels. When crowfunded documentary makers speak about their successful campaigns at film festivals, as Sørensen details, they appeal to a new form of social capital – support of the crowd, of the new safeguard and vower of quality. At the same time, their very participation in the festival strengthens their prestige in front of the audience. Some platforms, such as People for Cinema (now part of Ulule), have seen online funded productions competing for festival awards the likes of Cannes.

Where then, asks Sørensen, lie the new “aesthetic and editorial” authorities? What are the crowd’s criteria for validation and are they enabling new documentary makers to affirm themselves, or is rather that previously-earned prestige and credibility of established names that get funded anyway ? Instead of polarizing the type of documentaries and their budgets, how could traditional funding sources like broadcasters and festivals collaborate with the alternatives?

It would be interesting to see how similar concerns find their place in other countries, where documentary industries have witnessed different traditional funding scheme. We are looking forward to your suggestions and resources on the topic!

Bibliography:

Sørensen, Inge Ejbye . ” Crowdsourcing and outsourcing: the impact of online funding and distribution on the documentary film industry in the UK”. Sage Publications – Media, Culture and Society (2012): 725 – 743