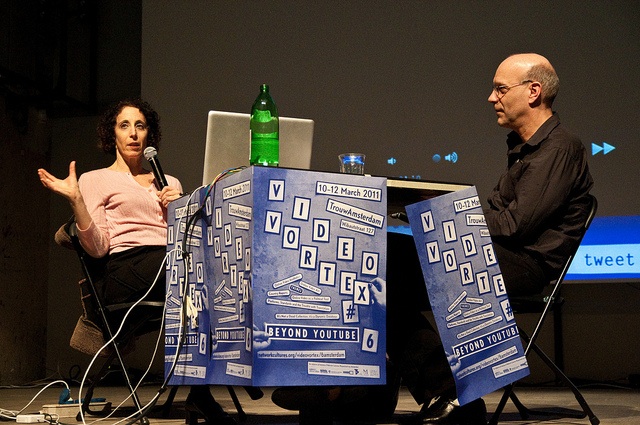

Artist Natalie Bookchin took time to talk to Geert Lovink about online video and her artistic practice at yesterday’s Video Vortex #6 in Amsterdam.

To open the conversation, Natalie screened Laid Off, a part of her series Testament, which offered a 4-minute impression of her work, capturing the current global financial situation and mass unemployment in the US.

Laid Off

[vimeo]http://vimeo.com/19364123[/vimeo]

Below is part 1 of the conversation we got to hear between Geert Lovink and Natalie Bookchin, and adapted to include further information.

G: You’re teaching at CalArts, you worked in the 90’s with the internet, developed games, and now suddenly you’re working with online video. How did you stumble into this?

N: I had also been very involved in thinking about online space as a site not only to make work but to distribute and exhibit it.

In the 90s I had been working, distributing, and exhibiting my work online. In 2005, I began to find the Internet too noisy and too crowded, and wanted to return to offline space in my work. I began to collect images from private security webcams that I found through a glitch in Google’s search engine technology which picked up thousands of webcams regardless of whether or not they are intended to be public. The cameras offered an unusual view of the contemporary global landscape mediated through surveillance technology. I became interested in depicting the world as it was described by the technology, and so rather than looking at the recording devices in the landscape, I looked through the cameras, drawing attention to the formal elements of this perspective, its odd and awkward angles of view and composition, its often fixed perspective, the limited tonal range, the dirty lens, and the distance from and limited contact or lack of relationship between the camera — which has no operator present — and its subject. From this material I developed, Network Movies, a series of videos and video installations that I made between 2005 and 2007, where I sampled data flows of images from webcams from around the world to create portraits of global landscapes. Limited bandwidth and cheap cameras produced jumpy, mechanical motion and grainy, low-resolution images that revealed their technological conditions and were reminiscent of early cinema. I began to make installations and videos offline, in order to provide a more embodied experience, absent in the distracted online space –with its small screen and potential for multitasking.

G: Your video work that uses online footage started with one installation didn’t it? When was the first one?

N: The first piece I made with YouTube footage was trip – a 63-minute single-channel video I completed in 2008, in which I documented a trip around the world using clips I culled from YouTube. From these clips, I pieced together a trip around the world from the point of view of tourists, human rights workers, locals, soldiers, and many others. The first point perspective put viewers in the position of a continually changing figure of the traveler, driving from tourist destination, across borders, and through war zones.

G: It’s a gallery installation piece with the look and feel of a collaborative global road movie. There you have your first experiences of making databases, how you select the videos and put them together. Let’s talk more about your approach. Now that we’ve seen Laid Off, it appears that it really must have been an enormous amount of work. It looks very complex. Technically, how did you do this? The syncing?

N: There is no database, nothing is automated – I simply searched, watched and collected the videos. For me, YouTube is in many ways a big heap of trash, out of which, with a lot of digging, treasures can be found. It’s not a platform so much as a site that hosts (and buries) videos. I don’t think it’s a community- so calling it social media is a misnomer. I don’t think there is conversation to be had on it through boxes for comments, or likes or dislikes. So I search.

I search for videos with an idea of what I hope to find, but I am often taken in unexpected directions. For example, with my current work-in-progress Now he’s out in public and everyone can see, I began with the idea that I was going do a piece about the reenactment and retelling of the recent Tiger Woods scandal. As I watched videos, I saw vloggers suddenly slip from discussing Woods, to Obama, or O.J. Simpson or Michael Jackson, or other African American public figures who had also been involved in media-driven scandals. As I watched and edited the videos and realized that the slips were key to the piece, it no longer became a piece about Tiger Woods, but instead about blackness as scandal. This was something I hadn’t known when I started the piece. The way I find and work with material is not and can’t be automated because it is through the process of searching and watching that I discover what it is I am making.

G: Ok, but let’s go back to your method, maybe you know the book by Richard Senatt, The Craftsman. When I think of you painfully putting this together, it’s like a digital craft, not using sophisticated software. But you use sophisticated ways to search for terms, in different languages.

N: Yes, for Trip I did search in different languages. In general, I use many combinations of keywords as I search, and I revise my search terms often as I develop each work. You’ve discussed in previous Video Vortex conferences the subjectivity of tags, which in some ways is very useful for me as I search, but it can also make it very difficult to find videos. I have many problems with the way YouTube structures its search engine – I’m not looking for the most popular videos, I’m looking for the most varied.

G: A lot of the videos you use are very personal. Are the people in these clips talking to family or friends?

N: Sometimes the vloggers make reference to other vloggers or to their subscribers, but mostly they don’t. They have all chosen to make their videos public – to make a public speech. Because of the layers of mediation, and because they are mostly at home in private spaces, their speech often becomes intimate, which creates a tension between the sometimes excruciating privateness of their speech and location, and the very publicness of the screening venue.

My Meds

[vimeo]http://vimeo.com/19588547[/vimeo]

N: In this one it’s not so much about the individuals, it’s much more about the choral group speaking together, in some way, in the other one there is a sense of individual personality that comes through at certain moments and then fades back into a collective voice.

G: Your work really reflects on theories of online subjectivity, new liberal labour and living conditions. It’s amazing to see this visualised. You can read a lot of books about the individual lives that people have, which you bring together in your work. Did this grow out of theoretical notions like the multitude, in which people retain their individual voices but are nonetheless part of something bigger?

N: In Mass Ornament I thought a lot about the relation of the individual to the collective, and the shift from Fordism to post-Fordism. Although I force a collective out of many separate individuals and spaces, the rectangular format of each video reminds viewers that ultimately each speaker, or dancer, is isolated. In this way my depiction of a collective remains partial, and produces a visual tension between the imagined collective and the isolated individual.

G: And that comes out best in Mass Ornament. It has that sentiment of them aspiring to dance together, even though they’re not aware of that when they’re filming themselves.

N: Yes, although many are in fact responding to other videos. In this way, they are dancing with an imagined community in mind.

—

End of Part 1.