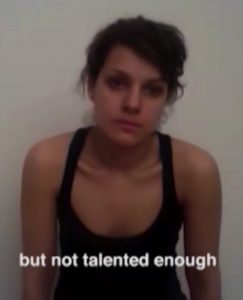

The Hungarian artist Judit Kis was one of the artists who gave a performance during Video Vortex #12 in Malta, in September 2019. This is where I was introduced to her very personal work. In the following months I engaged with her work and decided to approach her for an (email) interview. In an artistic sense, Judit Kis fits well into the ‘intermedia’ category. She produces videos (https://vimeo.com/user9166179), photo documentations (here her older Tumblr site), prints, paintings, ceramics, performances and installations consisting of blankets, lightboxes and bricks. She prints sentences on textile and engraves words into ceramic bricks (all in English). Titles of some of her video works: I have never happened, Detoxification, Dedication, Disillusion, Distance, I love you, and a confronting one: Enough.

I was interested in an online exchange with her because of my recent work on mental states such as sadness, anger and loneliness and how those moods are generated by specific algorithms that make you feel bad. Her website (https://u-dyt.com) states that Judit Kis’ practice deals with integration, self-revelation and healing. “In a form of ‘confessional art’ my aim is to create works that are embracing vulnerability and engaging my audience to connect themselves and others on a deeper level.” Her recent projects emphasize the importance of self-care and rituals in a contemporary context, reflecting to our diverse cultural heritage that became more accessible by technology. According to Kis “art has a transformative power in our thinking and especially if this art can be bodily experienced and show progresses in personal improvement.”

Take her 2017 ‘Cyberlove’ project, which consisted of an eight month long Instagram performance about a semi-platonic love affair, “a video installation with artificial fog, a series of emotional landscapes printed on Tyvek paper and a 2 sqm blanket.” Over the years we see her work evolve from diagnosis to therapy, from experimentation with the self through a radical public display of the artists’ uncertainty, to strategies of self-healing. Judit Kis put her self to the test. Her work is defined by a refined East-European dryness, precision, mixed with a grey absence of hope, where diminished expectations of a harsh neo-liberal society, life in general, and the Other in particular become rich resources for confronting, intimate art pieces. The following exchange took place right before and during the coronavirus crisis, in March-April 2020.

GL: Can you tell us something about your own evolution of the idea to ’embrace vulnerability’? Many artists would claim that they explore sensitivity in order to see the world with new eyes. This is probably not what you mean.

JK: I see ‘embracing vulnerability’ as the practice of compassion. It was one of my deepest fears to go into situations where I can get hurt or let others see me failing. When I could reveal my vulnerability in public, I felt like I became an agent and not only acting for myself. This way it was very empowering to go beyond my boundaries. At the time I started my practice in school, I felt encouraged to do socially engaged art projects even in situations where I had zero to a minor competence. I wanted to do art from the conflicts that were the most present in my life and perform where I can have the biggest impact. I was in the age of exploring my identity and while other topics seemed to require endless research, I had the full right to use my own stories as the source of my inspiration. Someone may consider the content of my videos too intimate, but I have never thought of my issues as something unique or too private. I started with small experiments like audio recording a conversation that I knew will lead to a break up, or hiding a camera to observe my reactions in certain situations. I found it very challenging from the beginning to talk about things that others are more silent about and when social media evolved with everyone projecting their perfected self-image, I just felt more urge to counterbalance the mainstream. Looking back at my ten year practice, I see how my topics come from childhood fascinations and traumas. The practice of overcoming my fear of others’ acceptance, taught me how to understand not just my vulnerability but others’.

GL: You have a new media arts background. How do you look at the current internet culture in the age of platform capitalism? You have yourself grown up with computers. What was the turning point for you?

JK: The early computer games and software available for us when I was a child were too ugly to be fascinating. I was lucky enough to grow up playing outside, maybe a part of that last generation. I didn’t spend much time in front of a computer until I was 16 and the first social media networks became popular. The turning point was probably my first MacBook, 10 years ago, that I used all day for work and in school like the extension of my body, a little window and also a mirror. I recorded almost every video I made with its web camera. I think there is really a gap between people who were born before and after the internet. I remember well when Hans-Ulrich Obrist launched ‘89+’. I was only 25 and still in school and I didn’t feel young artists count so much until then and suddenly they had to be under my age. Looking at the aesthetic and content of those selected works were very alienating for me. I felt like I grew up in a different world.

Today, I follow many artists also under the age of 25. I enjoy seeing their progress and how well they can use social media platforms to criticize our culture and to build a community around their work. I have to keep customizing my feed in order to reach their counterbalancing content, but it’s worth the effort. I am only active on Instagram on a daily basis where I have set up a time limit. I remember when I had 5-6 different sites where I shared my work, nowadays I find even my website unnecessary.

GL: How did you get to the concept of ‘self-healing’? Would you emphasize the ‘do-it-yourself’ aspect? Does this strategy come out of the institutionalized practices of therapy and fitness, sports, the yoga industry?

JK: No, it was rather rooted in my own practice. I wrote my thesis on identity construction and I created the videos to illustrate the work and improvement I made on myself. I’ve been using the therapeutic effects of making art. I referred to the words healing and self-care first, because they have become part of our everyday language and I thought it could help me to integrate what I was doing anyways. And yes, I would emphasize the DIY aspect, because we have great power to change things in our life and become better humans.

GL: In your recent art works such as Standards and Cyberlove you combine installation objects, paintings, videos and Instagram pictures in an overall ‘intermedia’ approach. Can you tell us about your findings? What works today, and what not? In your experience, which combinations of the real and virtual work?

JK: In the first six years I mostly created videos and later I had online performances, zines and public engaging programs during my exhibitions. I didn’t follow any strategy or rule with my work. I made things that I felt right, honest and I needed to release. I considered the objects I made as tools with symbolic meanings and I staged them in my video performances to express certain feelings. I’m not assigned to any gallery and I can’t say that my projects work in terms of an art practice that sustains itself, but many other ways I found them successful. I chose this career, because my intention besides sharing my work was to meet people, exchange ideas and find ways to collaborate. Through the brick project, Standards which I started only in 2017, I worked with many craftsmen and other professionals to produce over 50 pieces from different materials. I think of these objects as the extension of my virtual work and I like to play with them, build installations and get messy.

However, it’s exhausting to find ways to install, store, transport and preserve these objects for a person who lives in constant uncertainty. What I did within the frame of my Virtual solo show and live performance, also in 2017, can work very well even in the quarantine situation. It was an experiment to break the cycle of rejections and neglect from the art world and through that online event I could engage a much bigger and relevant audience than I did with many of my gallery shows. I am curious to see how the art market will change in this upcoming crisis and how it will affect the art institutions depending on it. For me it was very disillusioning already and I would have felt useless dreaming of a future show at a bienale or developing skills to promote my art. I find works the most engaging when they can create situations where I can experience empathy and connection with others. I prefer to have works that can be accessible for many, for example with a link. And by adapting myself to the circumstances, besides my mental well being I want to invest my energy into online education and organizing more community projects.

GL: How do you look back at your 2017 #cyberlove project?

JK: I remember that year was full of rejections and I felt very insecure. Referring to your essay, I think this project really comes from sad passions. Sadness is a very active feeling compared to ‘numbness’ that came later to my focus. I allowed myself to be sad and through the blog posts for eight months I left traces for future works. With sad passion it’s always possible to be productive through a symbolic projection of oneself. Even though they say sadness comes when we have no impact on our surroundings, I insisted that this sadness be inspiring somehow. It’s my second unique hashtag and I find these online performances stored on social media sites much more important than the foggy landscapes and video installation that came as a result.

(photo: Dávid Biró)

GL: What do you make of ‘digital detox’ weekends when stressed people try to forget their smartphone and force themselves to go offline?

JK: I have a dog who forces me to have a routine, go outside, pay attention, be determined. He changed my life completely and I often forget about my phone because of him. I like to spend time with my mom in her countryside home and sometimes I also go to long yoga and meditation workshops. The most recharging for me is when I can try things that I haven’t done before, for example organizing a party for friends who have babies to get involved in their life, or recently I took a shelter dog home for a weekend. As long as I can have these emotionally intense experiences without the involvement of technology, I don’t feel the need to go completely offline. There are times when I get more distracted by scrolling and looking at others, but I am aware of its negative impact on my productivity. I think it’s the key to originality, to look more inside.

GL: Your current topics are healing, self-care and contemporary rituals.

JK: I aim to explore alternative healing methods in different cultures that are less known or integrated. I would like to see the effects of these inherited traditions in our contemporary society, where technology rules our life but we seek to experience things that can help us to connect to our own body and mind. I research practices in the fields of psychology, religion and anthropology, but I also source inspiration from online videos and other communities. I am interested in what is accessible for everyday people who are desperate for help. I think experiencing artworks which deal with these topics can be very powerful in ways of transforming our beliefs. We should be reminded that we hold power over our life and we aren’t excluded from society when dealing with mental problems or other seemingly incurable conditions. As I perceive it, we all have something or someone to heal in our life. My self-healing journey started because of my mom. She refuses to go through medical treatments and I understand her concerns about relying on public healthcare.

(photo: Dávid Biró)

GL: When you talk about programming the brain, do you refer to neuroplasticity and the way Catherine Malabou is writing about this?

JK: I think not even in her elaborate research is it confirmed that we can substitute the biological with symbolic projections. I don’t feel enough confidence to connect neuroplasticity to self-healing directly, even though they are linked to the capacity of the brain to transform. It’s scientifically proven that emotional traumas can do physical damage to our body, but there is no medical evidence to confirm that positive experiences do the opposite. There are types of diseases that can’t be generated from a psychological trauma or at least not in the life of the patient. I am still at the very beginning of this project, but I know there are many cases when a patient healed without going through surgery and other medical therapy. (For example the artist Lynn Hershman Leeson explained in one of her video works that she could recover from a brain tumor by practicing pain meditation).

Hopefully, I will learn more about what kind of experiences and alternative therapies can motivate these recreational processes in the body, how to stimulate the brain to change its reactions, and how to encourage people to try these methods for healing. For instance ‘forgetting’ happens unconsciously in order to process certain traumas, but by ‘programming the brain’ I mean intentional practices like rewriting memories and deconstructing identities.

GL: Can you say something about the responses you get?

JK: I like to get feedback and opinions on my work, because they re essential in order to improve my practice. I feel more motivated when others express their openness or feel encouraged to reveal something about themselves in the environment of my work. I had a few encounters with strangers who got very emotional while looking at my performance and some of them indicated that it was empowering or enlightening in terms they could see someone else coping with the same issues. I experience more involvement when my performance is very rough and real, because these actions seem more honest in less designed circumstances. On the other hand, through the years I become aware of that, expressing vulnerability in public has another important ethical aspect. I‘ve learnt that for some people my acts could appear intimidating considering that they aren’t so open to confront their related problems.

I know exactly how much effort it takes to be on that certain level to expose things or sometimes to just wait until the right moment arrives. In the past I recorded materials that I could only process two years later and there were many ideas that I haven’t been brave enough to realize or commit to on the long term. I think it would be important, and useful, to create more space for confessional works, but organized in a very sensitive and inclusive way. The participants should feel involved enough to decide about their own limits, while they are also challenged to stretch their boundaries a bit further. In this way we could destigmatize many mental confusion regarding traumas and social constructions. As an opportunity to heal together.

(photo: Dániel János Fodor)

GL: You’re trying to figure out how to stay positive and “reverse the mess that is making people sick everywhere,” as you wrote to me. Is it important, then, to first make a proper diagnosis?

JK: Definitely. What concerns me is the numbness or indifference that we feel collectively. I am confronted every day with how much power we have lost in controlling our life, to decide about our future. I see the focus always on the things that we cannot change, like they want us to stay motionless and ‘sad’, as you write. I understand how these patterns are designed to exercise power over us and I want to inspire the opposite. We need to learn how to tell stories about the climate crisis, wars, poverty, violence, animal cruelty and viruses without paralyzing the audience. I see the solution in creating communities, deepening the connection between people and promoting art and other activities that can teach us how to care more about ourselves and others. I imagine rituals in a contemporary context to be very empowering experiences. For this reason, I’ve started to build a network for ‘confessional art’ practices and organize collaborative events. I find it important to honor those artists, who cast themselves as the subject of their art and practice self-revelation; it’s such a radical act to learn from. Through their workshops and performances they are more effective in creating safe spaces and engaging participants.

I’m not sure how things will change through the current corona crisis, but I decided to look at this quarantine time as an opportunity. I am staying with my mother and while I look after her, we can experiment on healing practices every day. Maybe I am less worried because this time is not the first for me to feel suspense. Social insecurity and financial uncertainty have been my everyday reality. Artists seemed especially in trouble at the beginning of this pandemic, but in the upcoming period millions of others will have the chance to experience this lifestyle. We need to practice solidarity and adapt ourselves as quickly as possible. I think artists will be the most creative in surviving this as we could never really rely on the system.